(All Rocket Manual for Amateurs scans from Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/RocketManualForAmateursByCapt.BertrandR.BrinleyBallantineBooks1960385s)

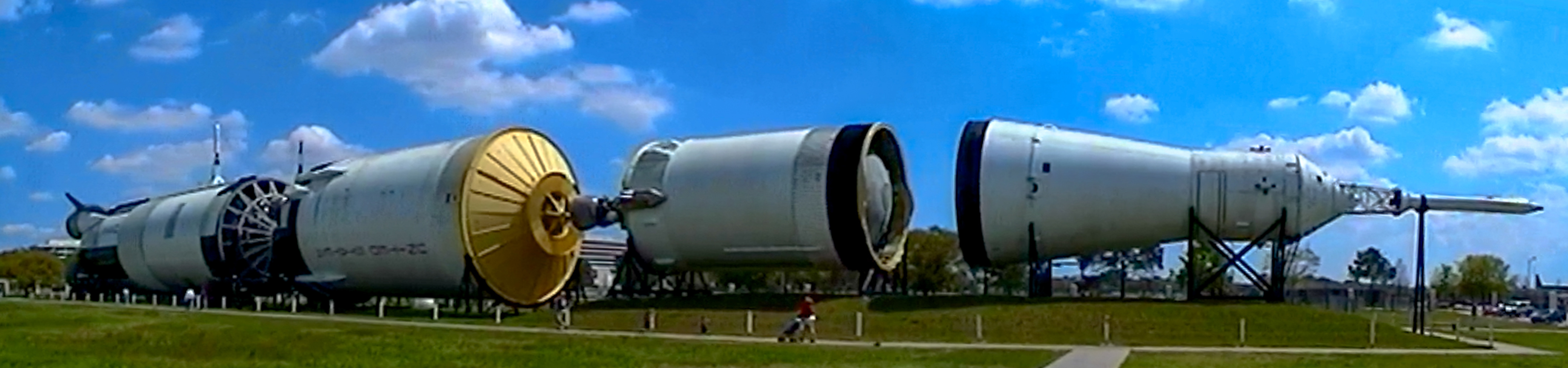

Rocket Manual for Amateurs, by US Army Captain Bertrand R. Brinley, is a remarkable book written at a very specific moment in time. After the launch of Sputnik in 1957, a craze for rocketry swept the United States, especially among teenage boys. But there was no straightforward way to build your own rocket in those days, so these boys muddled along, pillaging black powder from shotgun shells or fireworks to serve as propellant. Some of these would-be rocket engineers ended up getting badly injured by their poorly-designed rockets. But others got increasingly professional as their experiments progressed, and they ultimately built successful high-performance rockets. This period of time doesn’t have much cultural resonance now, but it is the setting of Homer Hickam’s memoir Rocket Boys (1998) and the film based on it, October Sky (1999).

I was born two generations too late for the post-Sputnik rocketry craze, but I also loved rockets in my youth. I happened upon Brinley’s Rocket Manual for Amateurs in a used bookstore in 6th grade and spent many, many hours reading parts of it over the next several years. I never did read the whole thing all the way through, though. Recently, I pulled it off the shelf on a lark and read the entire book, after not having opened it for at least two decades.

Bertrand Brinley was an Army public relations officer, the head of the First U.S. Army Amateur Rocket Program. The Army program and Rocket Manual for Amateurs were both conceived on the same premise: teenagers are going to experiment with rockets one way or another, so it’s better to teach them how to do it safely than to try to stop them. Not everyone agreed with this approach; the American Rocket Society officially condemned amateur rocket experimentation, and Brinley wrote an open letter to the society encouraging it to change its stance.

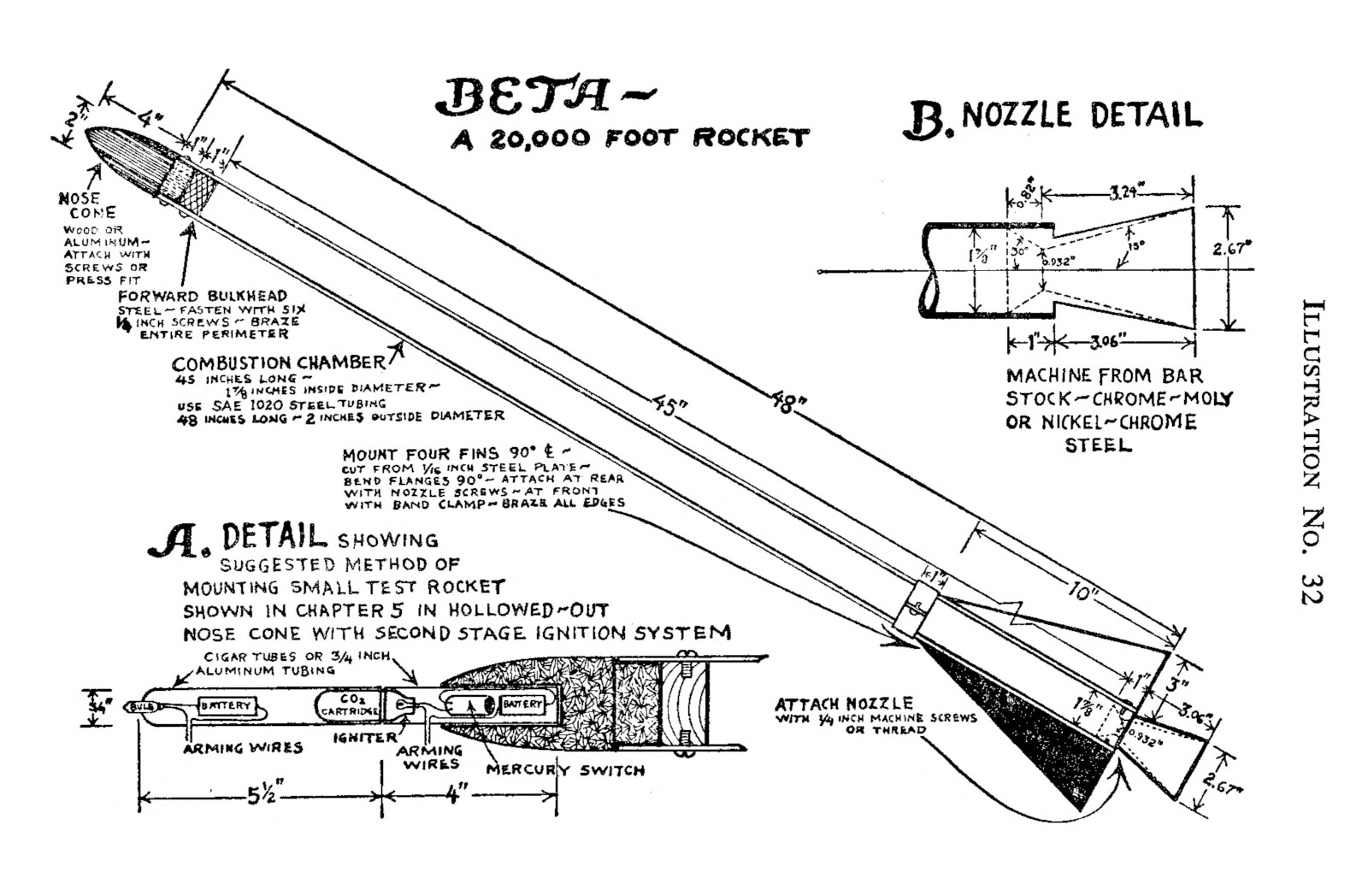

Rather than jumping right into discussing rockets, the first chapter of Rocket Manual for Amateurs explains how teenage rocket experimenters should get organized, by forming a rocket society, recruiting adult advisors (an overall sponsor and a technical advisor), and getting permission from local authorities and landowners to conduct their rocket experiments legally. Chapter 1 even includes a model constitution for a rocket society. The book next proceeds with a quick-start guide of sorts about how to build and launch simple rockets, using steel tubes or cigar canisters for thrust chambers and hand-mixing your own propellants. Subsequent chapters go into much more detail about all the major aspects of amateur rocketry, including propellants, rocket motor design, payloads, setting up a firing range, range procedure, and tracking.

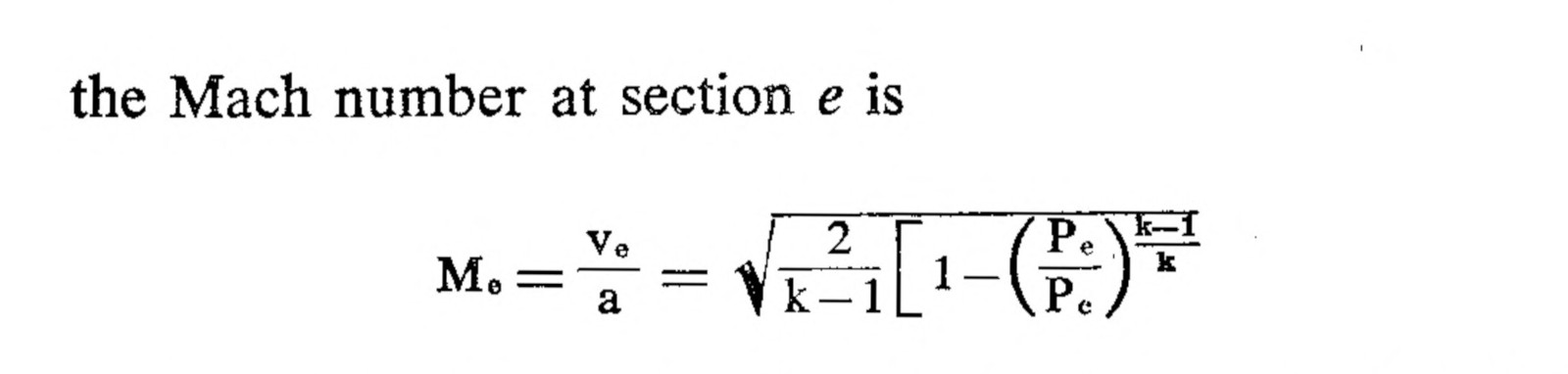

When I read this book as a teenager, I was frankly awed by the scary-looking equations in its pages, especially the ones for nozzle design in the chapter about rocket motor systems. I wanted to run those calculations myself, but I never could quite summon up the courage to try. When it came to math in high school, I was a mediocre student at best. Twenty years and one engineering degree later (my math got better in college), I can now see that the calculations in the book are actually pretty simplified. Trigonometry appears in somewhat simplified form, while there is not so much as a hint of calculus or any other higher-level math.

Brinley writes in a conversational style, with a bit of a fatherly tone. (He was in his early forties when he wrote this book. He went on to write a series of books for children called The Mad Scientists’ Club, which I have never read but surely would have loved if I had run across them in my used bookstore rather than Rocket Manual for Amateurs.) In the discussion of simplified rocket nozzle design (a few pages before those equations that awed teenage-me ever so much), Brinley writes:

If you can’t do square roots you can multiply the diameter of the throat by 2.64 to get the diameter of the exit for a 7 to 1 area ratio, or 2.81 to get the diameter of the exit for an 8 to 1 area ratio. However, you shouldn’t be designing rockets if you can’t do square roots yet.

This piece of advice has stuck with me ever since I read the book as a teenager:

If you would be a successful organizer and ‘run a tight ship,’ as they say in the Navy, then you must learn to apply two very simple, but inviolable rules:

Never establish a rule or regulation that is not entirely necessary.

Never establish a rule or regulation which you cannot enforce, no matter how necessary you feel it is.

This advice made an impression on me as well:

It is a good rule in life never to open your mouth the first time that an idea occurs to you. Think it over for awhile and consider it from every angle. After you have thought about it for a few hours, or a few days, and it still seems to be a good idea, then it is time enough to talk it over with someone else. You can save yourself and your group a lot of embarrassment this way; and you will earn a reputation as a sober thinker, rather than a blabbermouth.

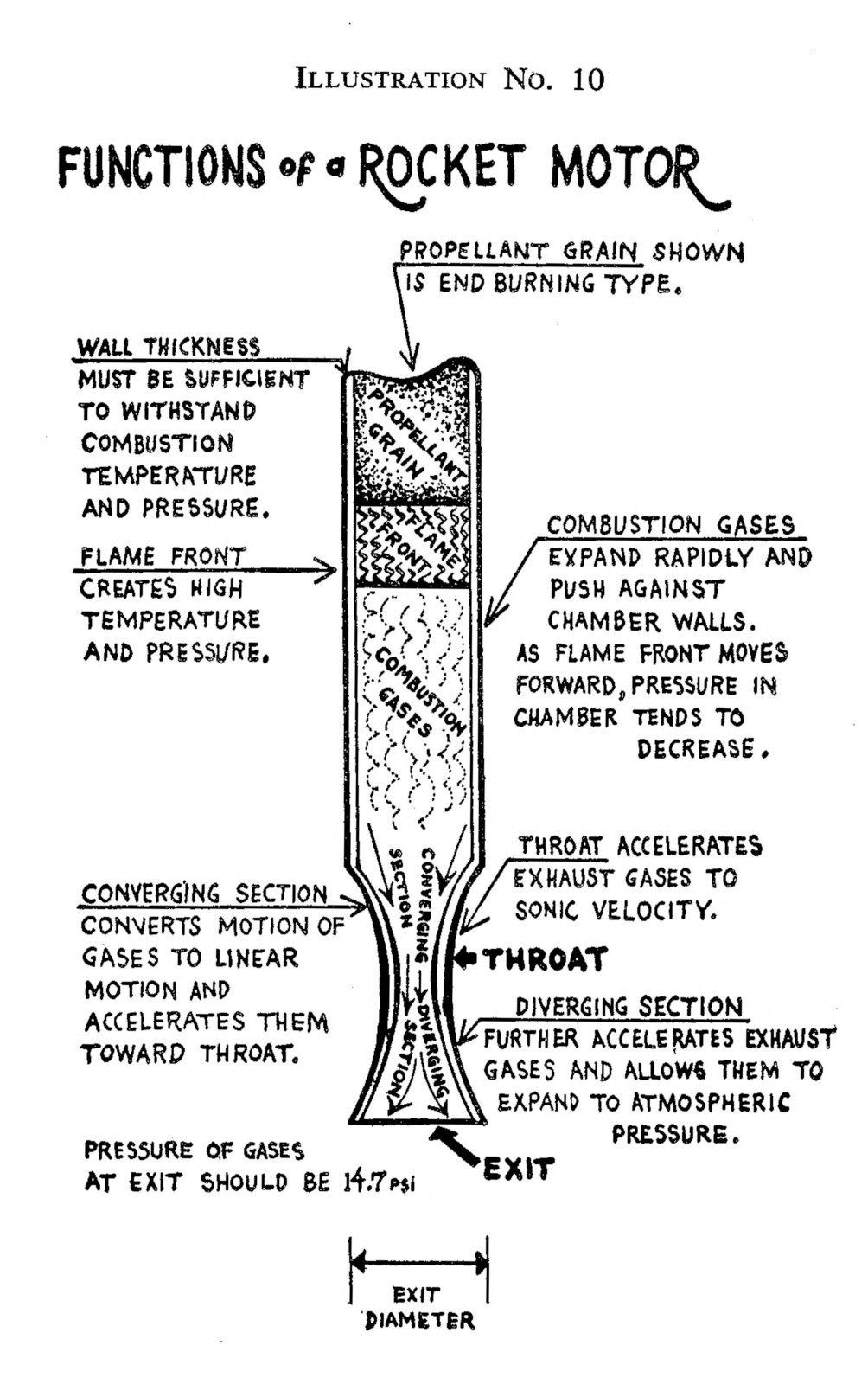

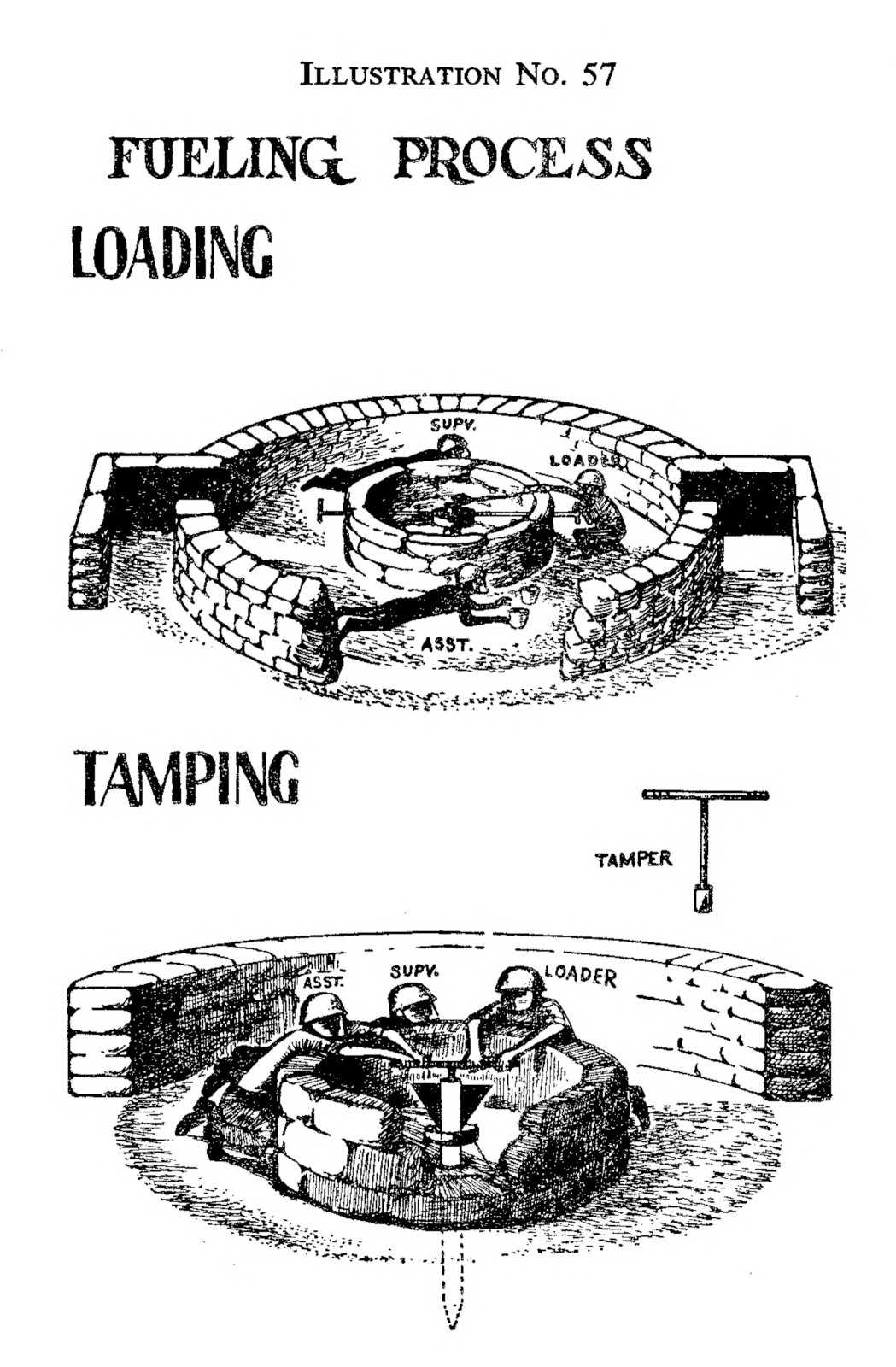

Another standout feature of the book are the illustrations, by Barbara Remington. They are clear and precise but also give the book warmth and character.

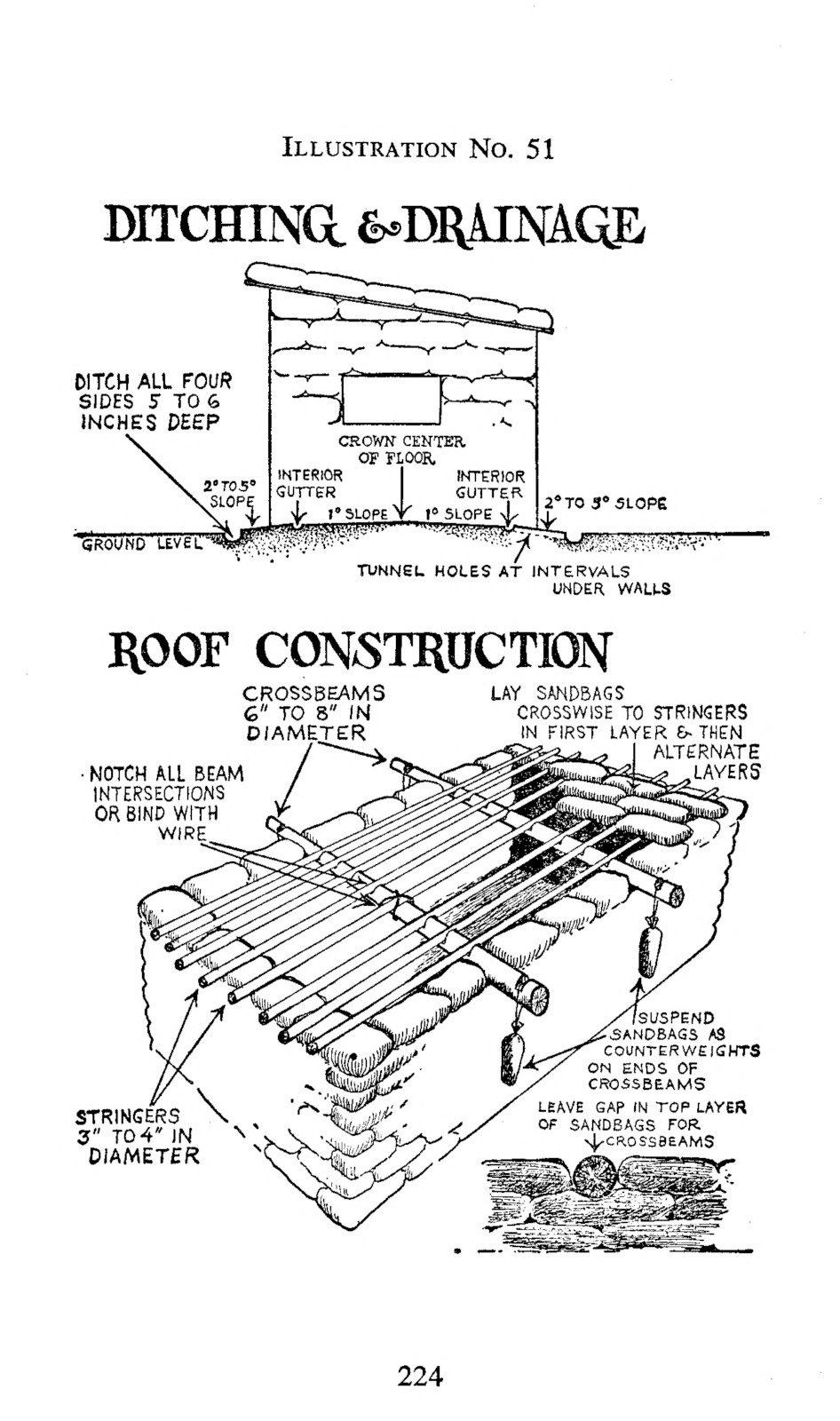

Overall, Rocket Manual for Amateurs definitely belongs to a different time. It is hard to imagine teenagers now having the discipline or the time to organize a rocket society, meet weekly, and build metal-bodied rockets from scratch. My generation never would have had the focus for that—and we were teenagers before social media and mobile computing. The America in this book is more coherent culturally and a good deal less crowded than the one of today. The ideal amateur rocket range described in the book occupies at least 12 square miles and has permanent structures including launching pit, fueling pit, five control center, guardhouses, and observation bunkers. I don’t know where you would find that kind of land now. I wonder how many former amateur rocket ranges are now occupied by shopping malls or housing developments.

This was a fun book to revisit, and I’m glad that I finally read the whole book all the way through for the first time.