This post is a follow-up to my piece from last year, “Remembering the United States intervention.”

The Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 was a hugely important event for both nations involved. At the end of the war, a defeated, humiliated Mexico lost nearly half of its territory. The United States gained this territory, including the strategic harbors of San Francisco and San Diego and the gold- and silver-rich Sierra Nevada. The aftermath of the war would lead to bitter civil wars in both countries, the War of the Reform in Mexico (1857-1860) and the American Civil War in the United States (1861-1865).

Given its importance, it is not surprising that the Mexican-American War is well-remembered in Mexico, with huge monuments in the capital and streets honoring the heroes of the war in cities across the country. In the United States, though, it is another story. There is very little cultural memory of the war, and virtually no monuments to it. (I am not including monuments to the Bear Flag Revolt in California, because the monuments never portray the conflict as a part of the bigger war.) I never even heard of the war before I was in 11th grade, and my students in college-level US History 1 know little or nothing about it.

Why do we not remember the Mexican-American War in the United States, even though it was so important? That is a question I have pondered for some time. I unexpectedly came across an answer to this question when I found an article about memory of the Mexican-American War while researching a different topic.

The article is by Amy S. Greenberg, and it appeared in the October 2009 issue of PMLA, the journal of the Modern Language Association. According to the article, it was between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the Spanish-American War in 1898 that Americans forgot about the war with Mexico. There were a couple of reasons why collective amnesia set in during this time. One was that the heaviest fighting in the war had taken place in territory that was still a part of Mexico, and there were thus very few soldiers’ graves on US soil to pay homage to on the new holiday of Memorial Day. (To this day, the US government maintains a cemetery of American war dead in Mexico City.)

There was also a political reason. In the Second Party System, the Democrats had been in favor of the war with Mexico while the opposition party, the Whigs, were opposed to it, seeing it as nothing more than a brazen land grab. (Great Whig statesman John Quincy Adams collapsed on the floor of the House of Representatives while railing against a proposal to honor the generals from the war with Mexico. He never recovered and died shortly afterward.) The Whig Party fell apart shortly after the war, splitting north and south over the issue of slavery.

In the North, most former Whigs joined the nascent Republican Party. After the Civil War, Whigs-turned-Republicans maintained their dislike of the Mexican-American War. From their perspective, the Civil War had been a righteous crusade to preserve the Union and liberate the slaves, while the war with Mexico had been a shameful attempt to seize more land for slavery. Republicans blocked the efforts of veterans’ groups to build a national memorial for the Mexican-American War or to preserve battlefields from the conflict.

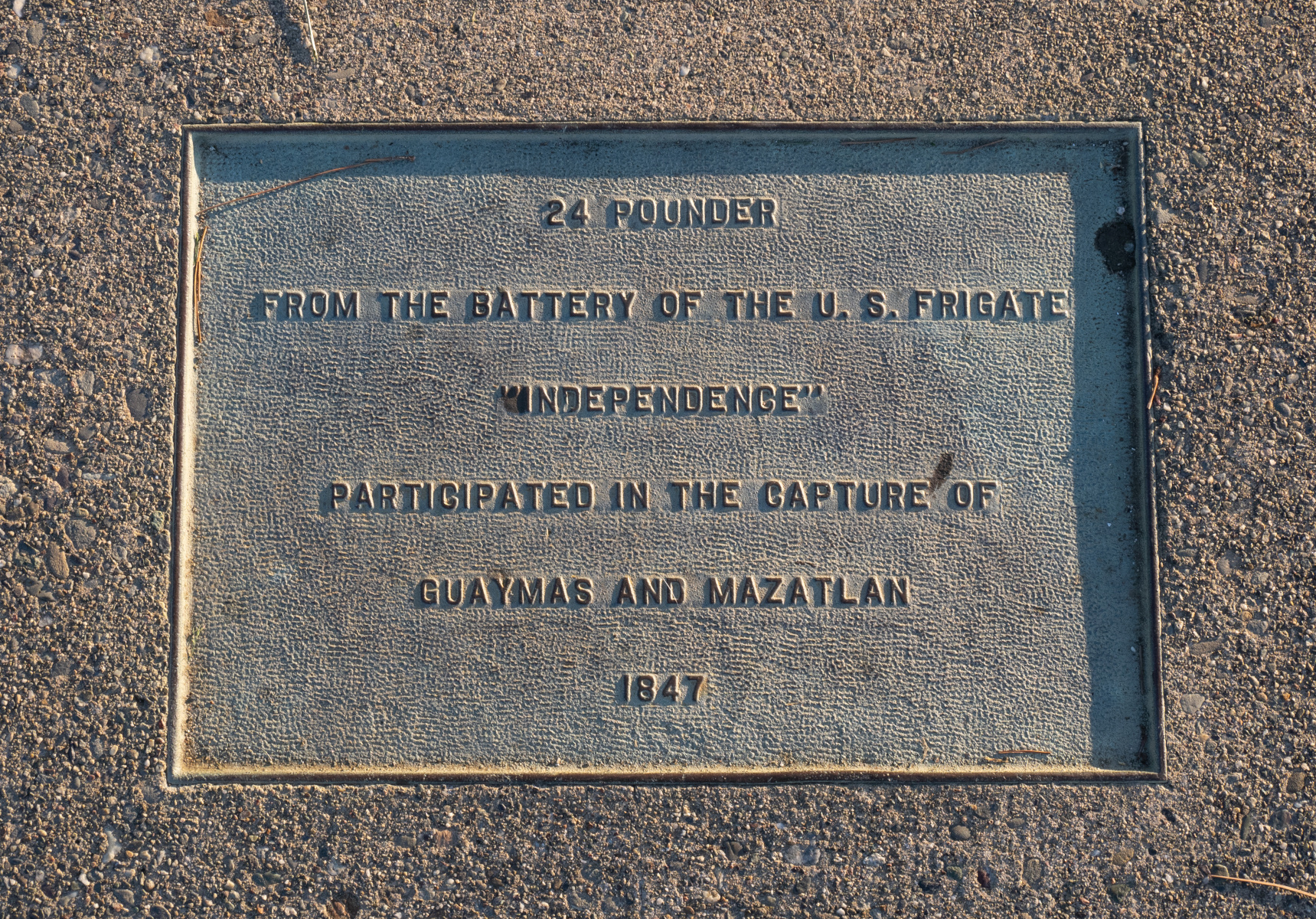

As it is, I have seen precisely one physical monument to the Mexican-American War on American soil, and it isn’t much of one. The waterfront in Vallejo, California, on the northern end of the San Francisco Bay, has a display of a couple of cannons. One of them has a plaque stating that the gun “participated in the capture of Guaymas and Mazatlan” in 1847.

And that’s it. If you want to see much more than this, you are going to have to go to Mexico!

The cannon from the USS Independence in Vallejo (foreground). The other cannon is a post-Civil War cannon from the USS Hartford.

References

- Greenberg, Amy S. “1848/1898: Memorial Day, Places of Memory, and Imperial Amnesia.” PMLA 124 no. 5 (Oct. 2009): 1869-73.

Links

- https://www.nps.gov/paal/index.htm Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Park in Texas. The first clash of the Mexican-American War took place north of the Rio Grande on land claimed by both countries. The battlefield was not preserved as a historic park until more than a century after the war.