(and not-so-little monuments)

On a street corner in Walla Walla, Washington, the town where I went to college, a gray stone soldier stands silently on a gray stone pedestal. Monuments like this blend easily into the urban landscape, and for years I didn’t pay any attention to it. When I passed by it, I simply assumed that it was a Civil War monument, based on the uniform worn by the soldier and ignoring the chronology. (The US Civil War ended in 1865 but Washington didn’t get statehood until 1889.) When, in my fourth year of college, I finally stopped to look at the monument up-close, I was startled to find that it was not for the Civil War but for the next big war in US history, the Spanish-American War.

Like the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War of 1898 isn’t much remembered or talked about in the United States anymore. But unlike the war with Mexico, the war with Spain inspired a frenzy of monument-building. Some of them, like the Dewey Arch in Madison Square, New York, were temporary structures, but many still stand, dotting the American landscape and blending right into it like the statue in Walla Walla. Once I noticed that this statue was for the Spanish-American War, I started to see monuments to the war all over the place. Here are some that I’ve seen and had the chance to photograph.

About the Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War took place over the course of just under four months in 1898, late-April to mid-August. The United States fought with Spain over its last remaining colonial holdings in the Caribbean, Cuba and Puerto Rico, as well as the Philippines. Because the war was over so quickly, it was nicknamed “The Splendid Little War” by people who didn’t participate in it, but it was in reality a bitterly-fought war, with American forces suffering high casualties from enemy fire as well as tropical diseases and conditions for which they were totally unprepared.

Before the war began, on February 15, 1898, the battleship USS Maine had blown up in Havana harbor, killing 261 sailors and sparking public outrage in support of a declaration of war against Spain. The fiercest fighting in the war took place in Cuba, as Spanish forces fought against Cuban revolutionaries and American forces that were supposedly supporting the Cubans. There was also a huge naval battle in Manila, in which the US Navy under the command of Admiral George Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet in the Philippines. In Puerto Rico, the Spanish forces surrendered without offering hardly any resistance.

After the war, Cuba gained its independence, but only nominally. The United States reserved the right to meddle in Cuban affairs whenever there was a dollar to be made. (This created resentment that led to Cuba’s communist revolution in the 1950s.) The Philippines became an American colony, although Filipinos themselves resisted US control for three years in a bitter, bloody insurrection that left thousands dead on both sides. The Philippines finally gained its independence from the United States after World War II. Puerto Rico also became an American colony, and it remains one to this day, having never been fully integrated into the United States or granted independence.

It isn’t hard to see why we in the United States don’t like to remember the Spanish-American War. Although this country has always been an imperial power, we were able to convince ourselves that our expansion across the North American continent was somehow inevitable (although it definitely wasn’t). But in the Spanish-American War, the United States became an overseas imperial power, just like Britain and France and apparently no better than them. In the end, we were probably worse imperializers. While France has legally integrated its overseas territories like Guadeloupe, Martinique, and French Guyana into France, the United States continues to refuse to make Puerto Rico a state or grant Puerto Ricans full citizenship rights unless they move to the mainland.

Relics of the Battleship Maine

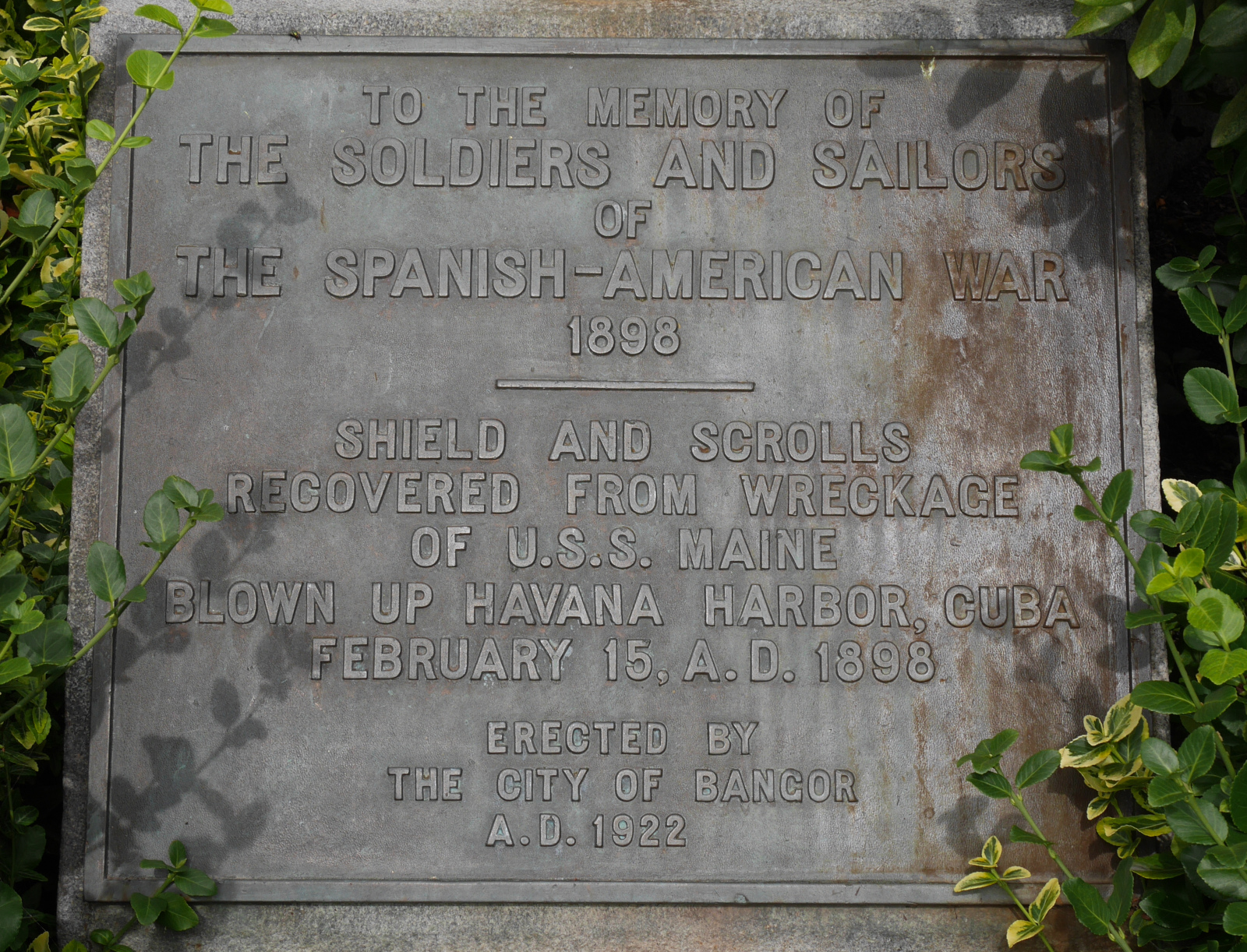

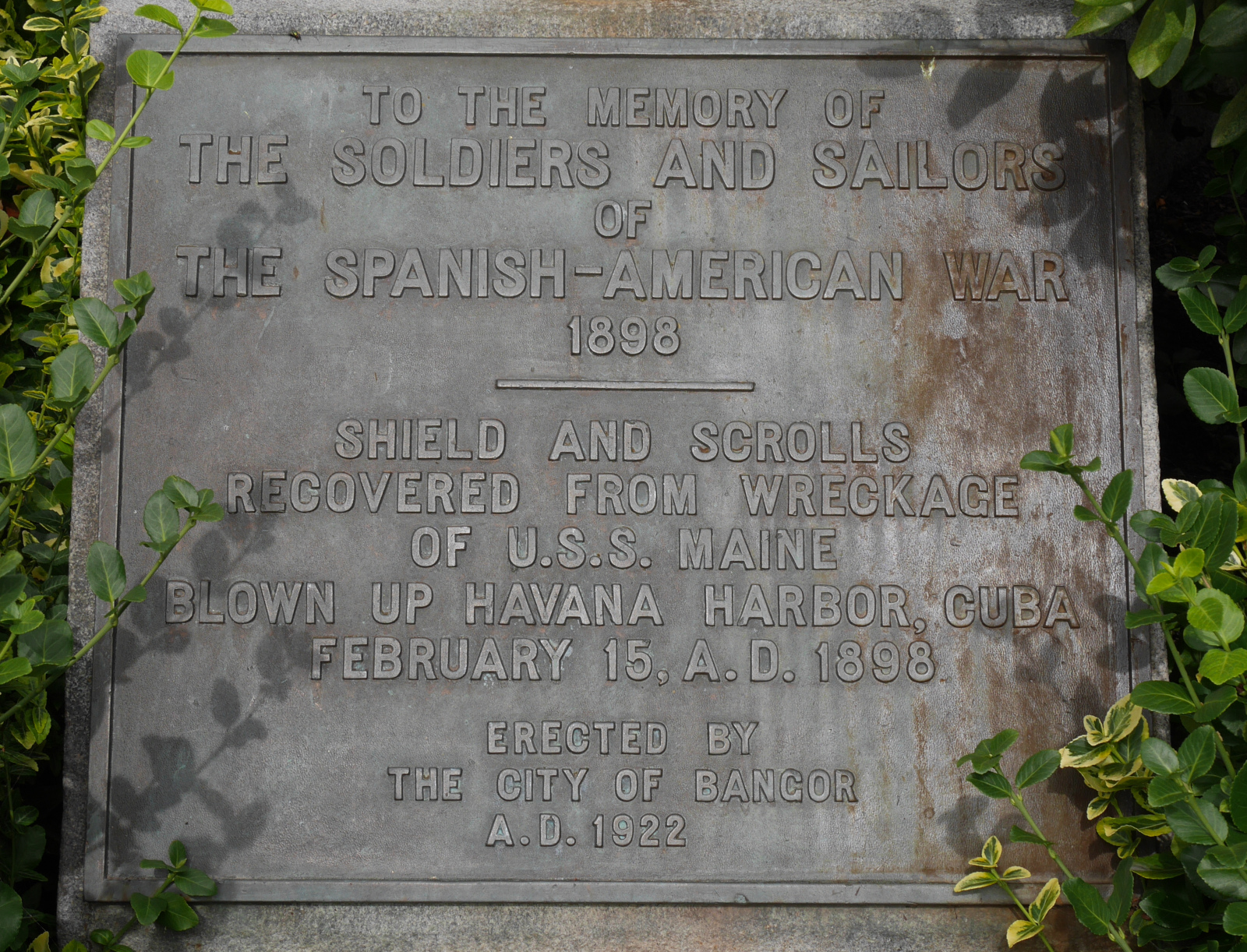

Parts were salvaged from the battleship Maine after it blew up, and some of them have found their way into permanent public monuments.

A mast of the Maine stands atop a monument in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Mast of the Maine in Arlington National Cemetery

Predictably, some parts of the Maine have ended up in the state of Maine. Portland has a gun from the Maine and Bangor has its impressive frilly bow decorations.

A gun from the Maine in Fort Allen Park, Portland, Maine.

The gilded filigree that used to decorate the bow of the Maine, on a monument in Bangor.

Detail of the shield from the bow of the Maine.

The plaque of the Bangor USS Maine monument.

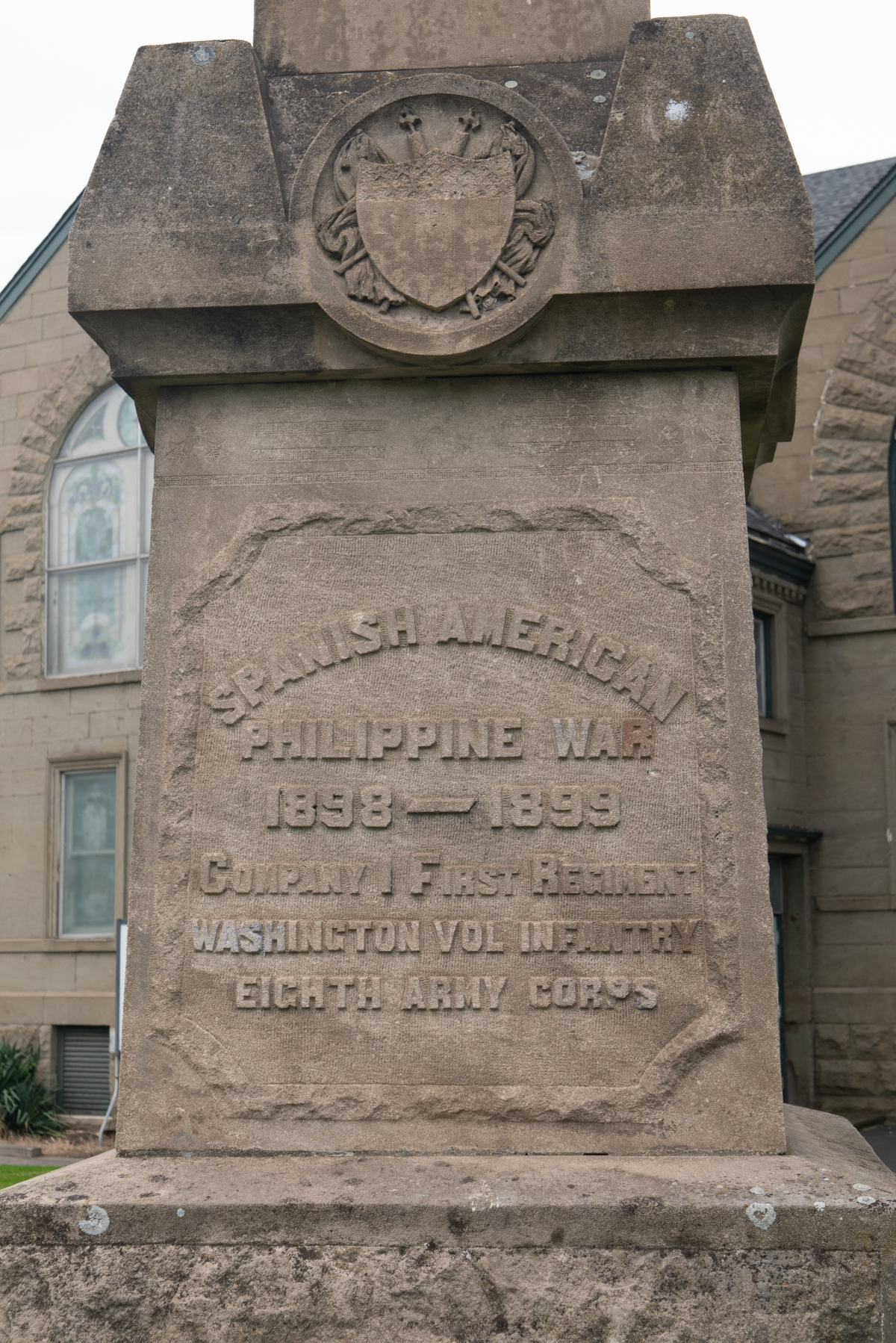

The monument in Walla Walla

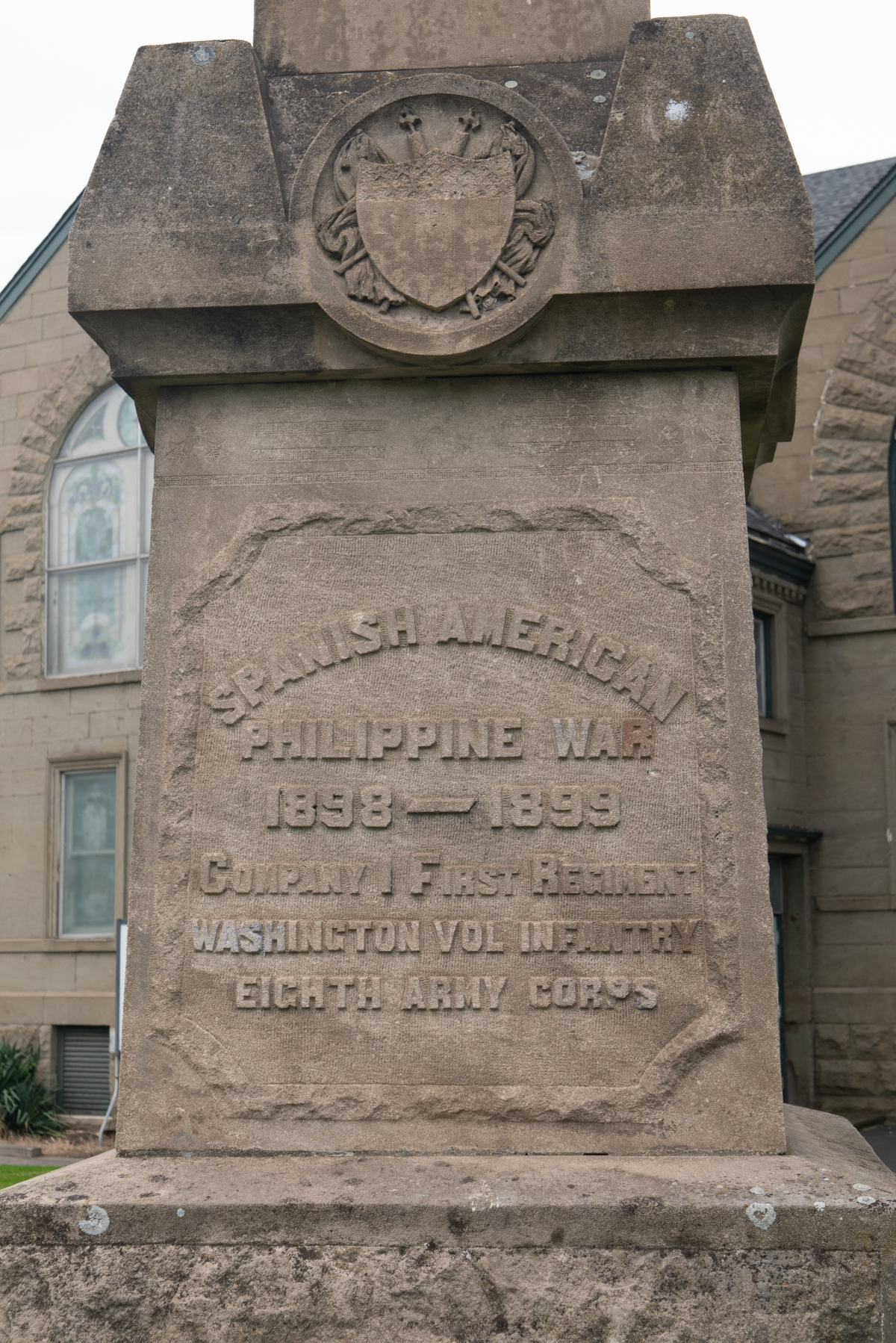

The Spanish-American War monument in Walla Walla honors Company I of the First Washington Volunteer Infantry. Being from a West Coast state, the regiment shipped out to the Philippines rather than Cuba. It arrived after the Spanish had surrendered, but it participated in the fierce fighting with the Filipinos. It was dedicated in 1904.

View of the Spanish-American War monument on Alder St. in Walla Walla, Washington.

Detail of the front inscription of the monument.

Detail of the inscription on the right side of the monument, with the dates and places of battles that Company I fought in during the Philippine War. An inscription below this declares that the unit was “204 DAYS ON FIRING LINE.”

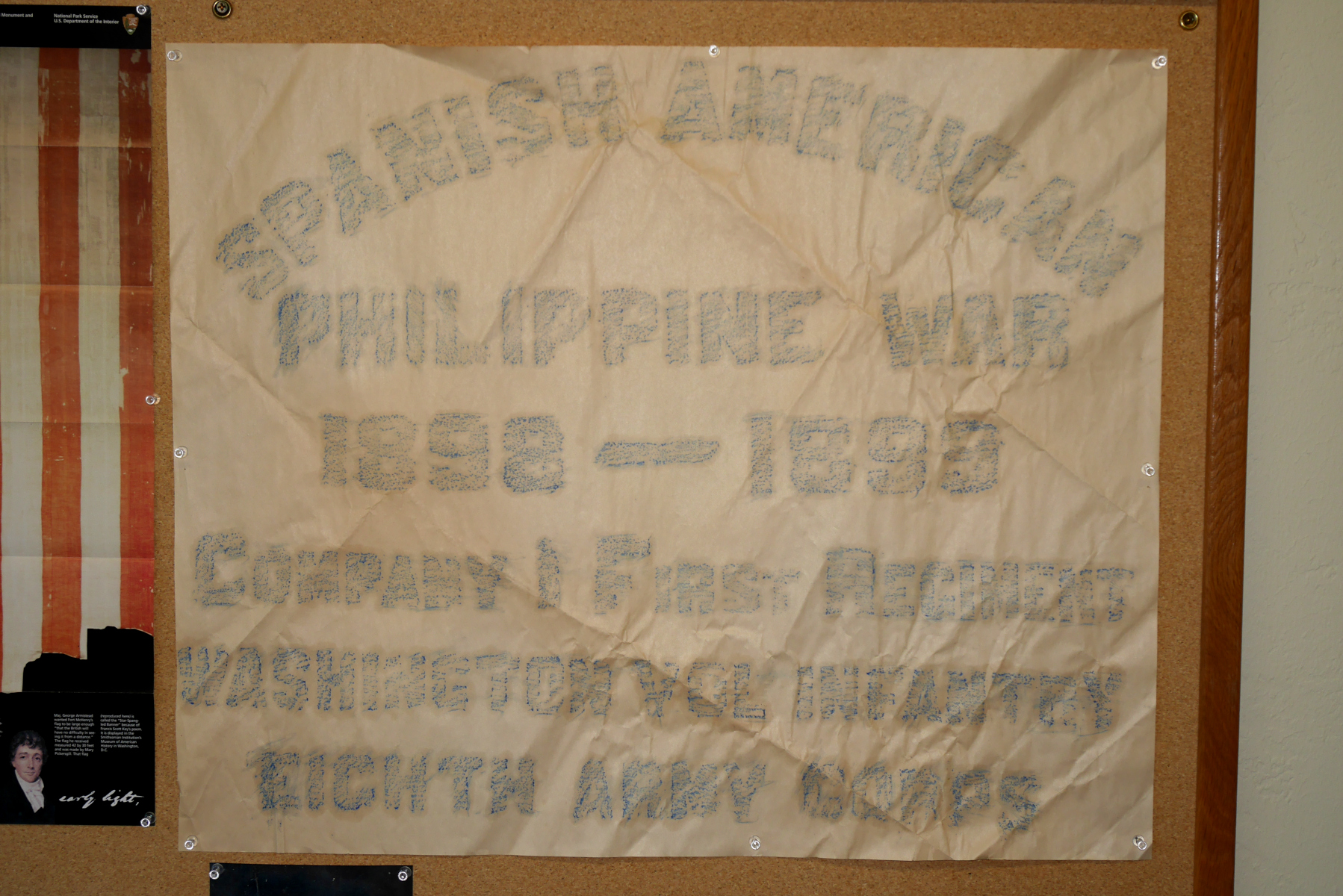

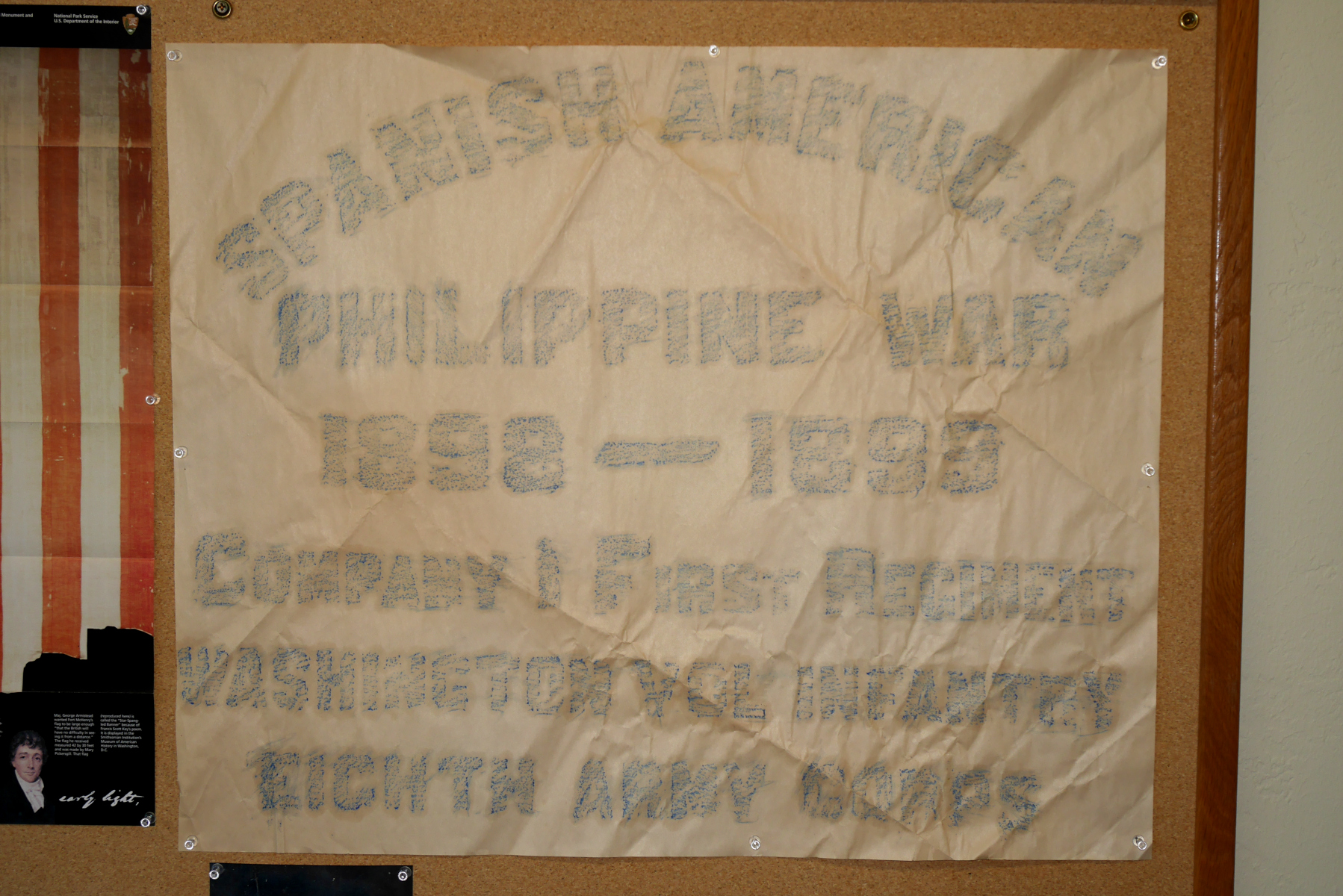

With the help of my mother, I took a rubbing of the inscription on the front side of the monument on Memorial Day weekend last year. It now hangs on the bulletin board in my office.

Dewey Monument in San Francisco

The biggest Spanish-American War monument I have seen is the Dewey Monument in San Francisco’s Union Square, which honors the hero of the Battle of Manila Bay. The Dewey Monument is an 85-ft-tall monumental column, crowned by a statue of the goddess of victory carrying a trident. It is an impressive monument, but it blends imperceptibly into the urban environment. The vast majority of shoppers at Macy’s and the other stores on the square probably have no idea what the monument represents.

The Dewey Monument in San Francisco’s Union Square. It was dedicated in 1903.

There is also a statue honoring Spanish-American War veterans on the grounds of the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

Spanish-American War veterans monument in Sacramento.

Bonus: Wheeler Dam on the Tennessee River

Wheeler Dam is a Tennessee Valley Authority dam in northern Alabama, and I have already profiled it in “A gallery of Alabama dams.” Of course, strictly speaking, this isn’t a Spanish-American War monument, but I include it here because it is named after a prominent officer from the war, General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler, who commanded troops in Cuba. He had earlier been a Confederate officer in the Civil War.

Panoramic view of Wheeler Dam in northern Alabama.

Links