It turns out that one of my favorite children’s books growing up is a story about history of technology, although I didn’t realize this until I was an adult.

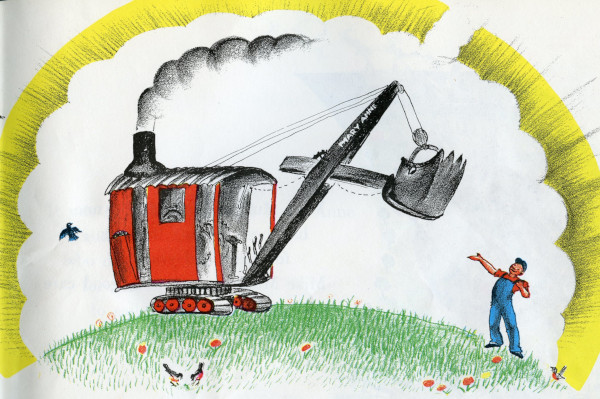

The book is Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, written by Virginia Lee Burton in 1939. In the book, Mike Mulligan owns an anthropomorphized coal-powered steam shovel named Mary Anne. For years, Mike and Mary Anne had been at the top of their game, digging canals, building highways, and excavating the foundations for skyscrapers. But then along come newer, fancier shovels powered by diesel, gasoline, and electricity. Mike starts to have trouble getting work for Mary Anne, because old-fashioned steam shovels are no longer wanted at construction sites.

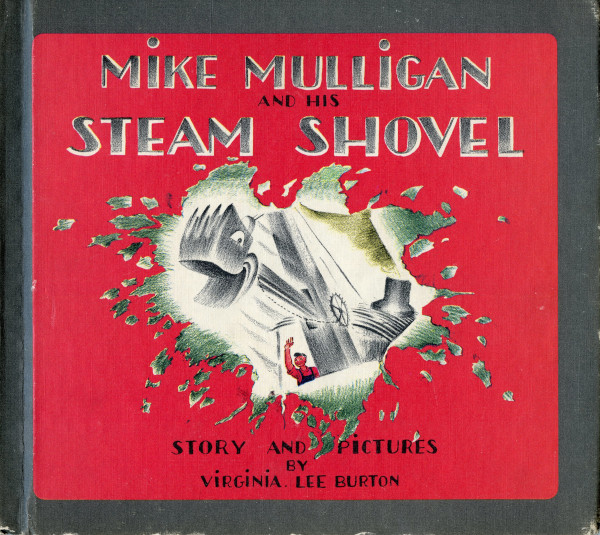

The cover of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, by Virginia Lee Burton. © Houghton Mifflin Company.

At length, Mike finds a job digging the foundation for the town hall of Popperville, a small town a long ways away from the big cities. At the end of the job, Mary Anne gets stuck in the basement of the town hall, because Mike had neglected to leave an exit for the steam shovel in his his haste to dig the foundation. Mary Anne ends up staying there and being repurposed as the boiler for the heating system of the building.

Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel is a story of technological change and adaptive reuse. The introduction of gasoline, diesel, and electric shovels represents technological change. With the newer, higher-tech shovels available, steam shovels come to be seen as obsolete and undesirable.

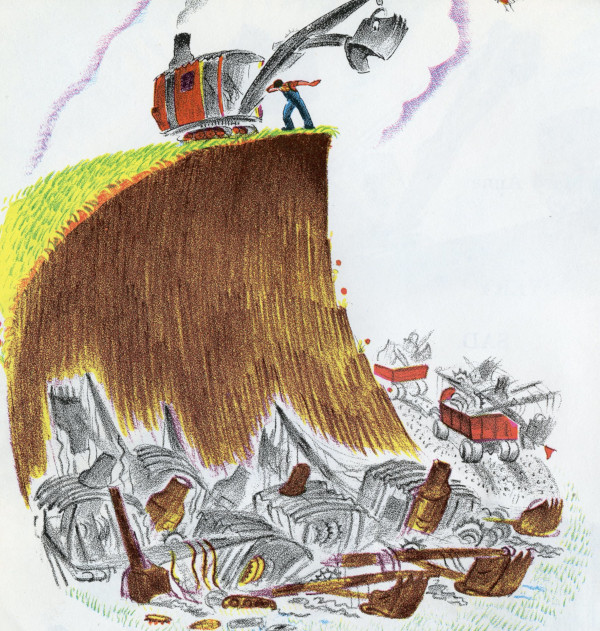

What to do with obsolete technology? One solution is just to throw it away. That happens to many other steam shovels; on one page of the book, Mary Anne and Mike look down in horror into a ravine where other steam shovels have been dumped to go to rust. “Mike loved Mary Anne,” the book says. “He couldn’t do that to her.”

A technology considered obsolete in a high-profile market might still be useful in a marginal market. I have written plenty about how supposedly obsolete technologies like ox-driven plows and VCDs live on in the Garo Hills of northeast India (or at least did ten years ago). In the same way, Mike could find work for Mary Anne in a small town, Popperville, after being pushed out of higher-profile markets like canal-building and skyscrapers.

At the end of the book, Mary Anne finds a more meaningful retirement than rusting to oblivion: as a steam heater in the Popperville town hall foundation that she dug. This is an example of adaptive reuse – finding new uses for old things that can no longer be used for their original purpose. Adaptive reuse provides a sense of continuity and is an example of what Kevin Lynch calls “wasting well.”

I would like to think that I first learned the value of adaptive reuse from Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel as a child. Whatever the case, adaptive reuse is a value worth learning, for children and adults alike.