Sixty years ago today, for the first time in history, a human boarded a rocket and flew into the cosmos beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. The first-ever traveler into space was a 27-year-old Russian pilot named Yuri Gagarin, and he embarked on his cosmic journey from the Tyura-Tam missile range in the Kazakhstan region of the Soviet Union.

By any measure, Gagarin’s flight was a remarkable technical accomplishment. In a matter of decades, Russia had gone from an agrarian country ruled by Europe’s last autocrats to the world’s first space power. In the 1930s and 1940s, Soviet engineers had made modest progress with developing rockets, primarily for military use but also to pursue the dream of human spaceflight first expressed by Russia’s pioneering space visionary Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who died in 1935. After World War II, captured German rockets and some German engineers provided valuable technical knowledge to the Soviet rocketry program. In the late 1940s, the Soviets flew copies of the German V-2 missile, which they called the R-1. Later, they modified the design of the R-1 into the higher-performance R-2 missile, then set about to make their own wholly original designs. By 1957, the Soviets had the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile, the R-7. After a couple of successful test launches, an R-7 deposited into orbit the world’s first artificial satellite, PS-1 or Sputnik 1, on October 4, 1957.

The R-7 had the power only to launch small payloads into orbit, but a modified version with an added upper stage could launch a spacecraft big enough to carry a man. The rocket and the spacecraft were both dubbed Vostok (“East”). The spacecraft consisted of two parts: a spherical crew compartment and a cone-shaped instrumentation module. The crew compartment carried the cosmonaut (“traveler to the cosmos,” a Soviet or Russian astronaut) into space and back down into the atmosphere, while the instrumentation module was designed to separate from the crew compartment and burn up in the atmosphere on reentry.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union were preparing to launch people into space in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but the two countries took different approaches to their programs in many respects. One of these was publicity. As I’ll write about next month on the anniversary of the first American’s flight into space, the US government conducted its space program in full view of journalists and the public, and the first astronauts were made into instant celebrities.

The Soviets, on the other hand, operated their program in the utmost secrecy. They didn’t even announce the launch of Sputnik 1 until after the satellite had completed its first orbit of the Earth. (Meanwhile, the first American attempt at launching a satellite, Vanguard 1, blew up on television.) While the American astronauts blinked in the daily glare of spotlights and flashbulbs, the first group of Soviet cosmonauts were selected and began training in secret. As the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin would become a celebrity—paraded in Red Square in front of adoring Soviet crowds and sent on international tours—but it was only after his launch that the public even knew his name.

Because of this secrecy, the Soviet public and the wider world could only know about Vostok and other early programs through Soviet propaganda, which portrayed every cosmonaut as a model communist and every mission as a triumph of socialism. It would not be until thirty years after Gagarin’s flight, with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, that the archives would start to open, giving researchers the chance to view actual documents rather than propagandistic distortions.

In the intervening thirty years, as Asif Siddiqi notes in the preface to his book Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974, early Soviet space accomplishments had become mythologized in Russia and dismissed in the West as mere background to the first American landing on the moon in 1969. “It is not surprising that this is so,” Siddiqi writes. “With little film footage, paranoid secrecy, and no advance warning, the Soviets themselves were mostly responsible for consigning these events into that blurry historical limbo between propaganda and speculation. They eventually lost any claim to resonance that they might have had otherwise.”

As the anniversary of Gagarin’s flight, April 12 is celebrated as Cosmonautics Day in Russia and by some space enthusiasts around the world as Yuri’s Night (although if you ask me, I prefer to call it Cosmonautics Day). There will certainly be official commemorations of the anniversary in Russia today, and just as certainly there won’t be any commemoration of it on an official level in the United States. Rather than seeing the flight as a human accomplishment—the first time in history that a member of our species left this planet—Americans continue to view Gagarin’s flight through the lens of Cold War competition.

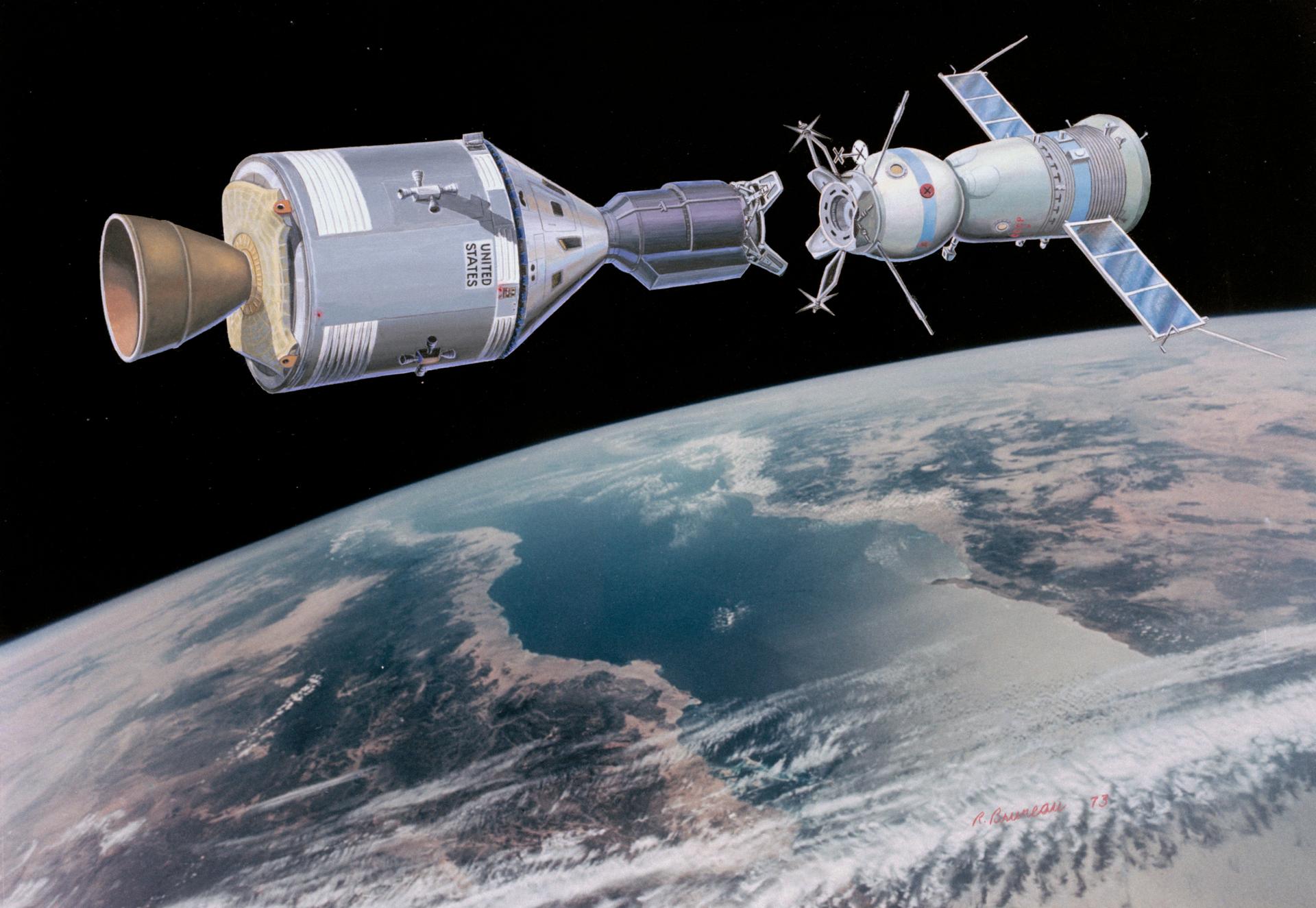

The Space Race continues to dominate American perceptions of the Space Age, even though there has been far more cooperation than competition between Russia and the United States in human spaceflight. The Space Race lasted at most thirty-four years, from the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957 to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Even during the period of competition, US-Russian cooperation in space began with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. After the fall of the Soviet Union, space cooperation continued with Shuttle-Mir in the 1990s and the International Space Station from 2000 to present. Rather than seeing Yuri Gagarin as a Cold War enemy, it’s time for Americans to start thinking of him as a future friend in space.

The first joint US-Russian space program was the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975, launched during the period detente in the Cold War. A Soyuz spacecraft from the USSR and an Apollo spacecraft from the United States linked up in orbit and the crews exchanged greetings and visited each other’s spacecraft. This is a group photo of the two crews, the Americans on the left in brown and the Soviets on the right in green. (NASA photo)

An illustration of the Apollo spacecraft (on the left) linking up with the Soyuz in ASTP. (NASA photo)

Space shuttle Atlantis docked with Russian space station Mir during the Shuttle-Mir program, July 1995. The Shuttle-Mir program ran from 1995 to 1998. (NASA photo)

After Shuttle-Mir, joint crews took up residence on the International Space Station, starting in November 2000. Here the Expedition One crew are seen visiting Red Square in Moscow. The Russian crew members are on the left and right and the American member is in the center looking at the camera. (NASA photo)