In southern Rajasthan, thirty miles south of the city of Udaipur, twenty square miles of the Aravalli Mountains have been flooded by the remarkable Jaisamand Lake, formed by the 1500-ft Jaisamand Dam. Tourist guidebooks frequently erroneously refer to Jaisamand as the second-largest artificial lake in Asia. This is far from the truth; in India alone, a half-dozen artificial lakes are much larger than Jaisamand. What is remarkable about Jaisamand is the combination of its size and its age. The lake was built in 1685 on behalf of Maharana Jai Singh of Mewar. Jaisamand holds the undisputed distinction of being the largest extant pre-modern artificial lake in India.

Of the numerous Rajput kingdoms in medieval western India, Mewar was the last to submit to the Mughal Empire. In 1568, Mewar lost its capital Chittaurgarh to the army of Akbar after a long and bloody siege, but a royal remnant escaped to found a new capital at Udaipur. The Mughals tried to defeat Mewar again at the epic Battle of Haldighati in 1576, but Maharana Pratap Singh escaped with his life and his kingdom. (Alas, Pratap’s horse Chetak succumbed to his injuries during the battle, but he has since become a local hero in his own right.) Finally, in 1615, after a series of battles, Maharana Amar Singh was forced to accede to the Mughal Empire. This was more than fifty years after Amber became the first Rajput state to join the empire.

After getting dragged into the Mughal Empire, Mewar could redirect some of its resources from militarization to infrastructural development. Jaisamand Lake was one of the public works projects undertaken in the post-accession period. The lake stored water from the Gomti River, for use in irrigation. It also provided a setting for palaces and royal hunting reserves.

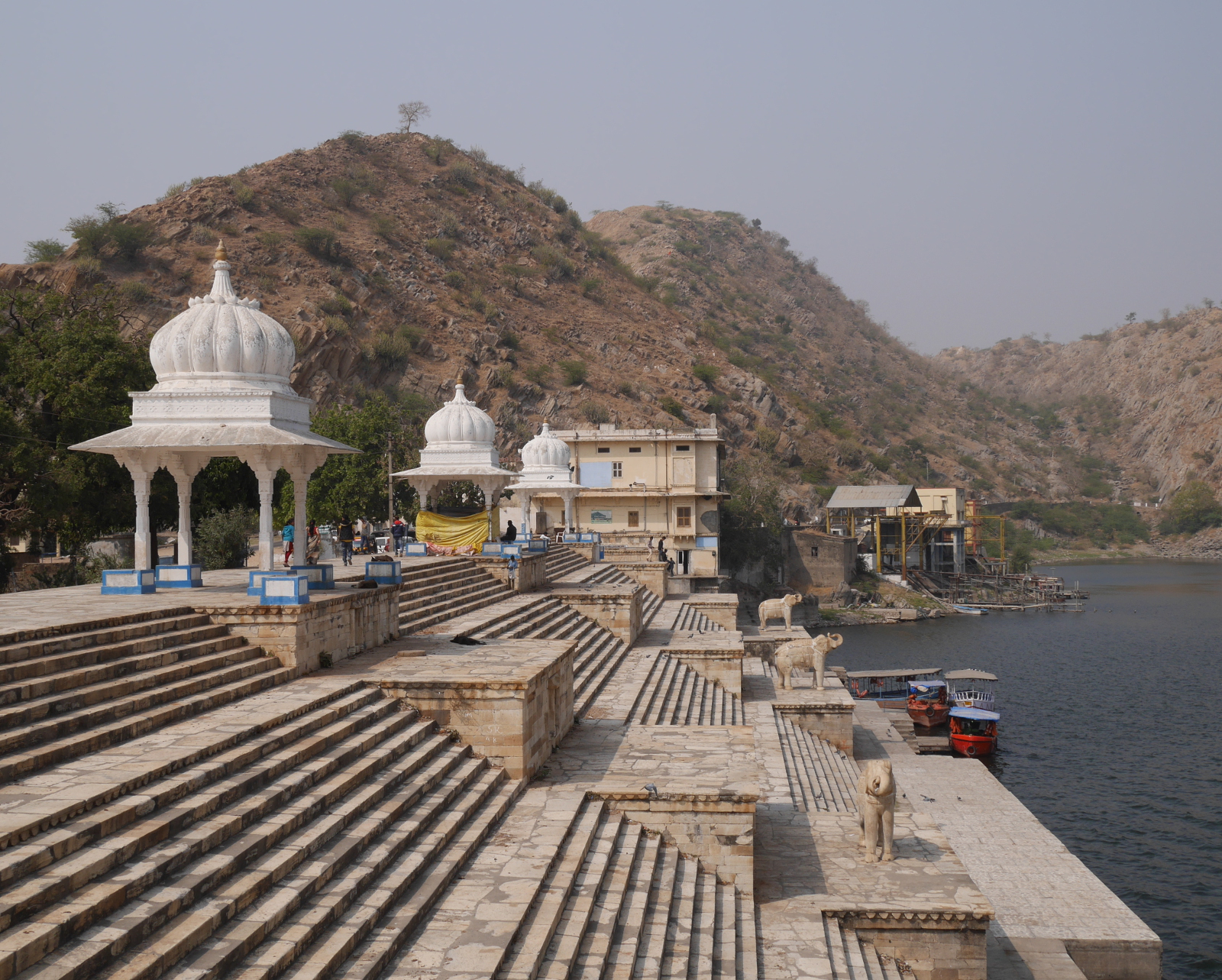

Jaisamand Lake has changed a little since the late seventeenth century. The original dam was refurbished around 1960. During the refurbishment, the historic front face of the dam was covered by a characterless concrete facade. The crest and backside of the dam, though, retain their historical appearance. A series of white marble steps lead down to the water. There are six stone chhatris (domed pavilions), six carved marble elephants, and a temple, Shri Narbdeshwar Mahadev Jaisamand. Despite some graffiti on the elephants, and the usual litter, Jaisamand Dam remains a place of historical importance and real beauty.

One of the chhatris on Jaisamand Dam. The white mark underneath the chhatri indicates the level reached by a flood in 1973.

Pigeons fly over Shri Narbdeshwar Mahadev Jaisamand Temple, located front and center on Jaisamand Dam.

Jaisamand is accessible from Udaipur by Banswara-bound bus from the main government bus terminal near Udaipol. The dam and the lake are just up the hill from Jaisamand town, where the bus stops. Boat rides are available from the dam, at Rs 600 per boat for a half-hour or Rs 1200 for the full hour. On a hill just above the dam, a ruined palace stands on forest department land. Visitors can get permission to climb up to the palace from the forest department office, with payment of a fee. I thought the rate for foreigners of Rs 300 was ridiculously steep – even without the additional Rs 900 camera fee – so I opted out of that experience.

For further coverage of India’s pre-modern artificial lakes, please see my posts “Goodly Lakes” and “Another Goodly Lake.”