Notre Dame on fire. (Source: Wandrille de Préville on Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0)

On Monday this week, the iconic Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris caught on fire. In what appears to have been a freak accident related to restoration work going on at the time, the cathedral’s medieval wooden roof caught fire and was totally destroyed. Initial news reports indicated that the entire church would be destroyed, but the bell towers were spared and the stone vaults over the nave remain mostly intact.

With this much of the structure remaining, it is obvious that the great church can and should be rebuilt. While the structure was still smoldering, French President Emmanuel Macron vowed that the people of France would rebuild the beloved cathedral.

How to go about the reconstruction is another question. It will clearly be an expensive undertaking that will entail many difficult technical and aesthetic questions. What materials and techniques should be used for the reconstruction? And what should it look like?

Some articles and editorials I have read assert that the church should be rebuilt exactly as it was before, even using the very same techniques used in the 12th and 13th centuries, such as erecting giant wooden frames in the nave for reconstructing the damaged sections of the vaults. I do not see the point of this. The High Middle Ages, when Notre Dame of Paris was built, was an era of technological innovation, with extensive use of machinery and even fossil fuels. If they could know, the master builders of Notre Dame would understand if we used steel scaffolding to rebuild their church.

In the same way, I feel that it is important that the rebuilt roof of Notre Dame should not be a slavish copy of the original. The spirit of Gothic architecture is one of creativity and inventiveness. President Macron expressed this spirit well when he declared that Notre Dame would be rebuilt more beautiful than before. Doing otherwise would be contrary to the spirit of Gothic and the High Middle Ages.

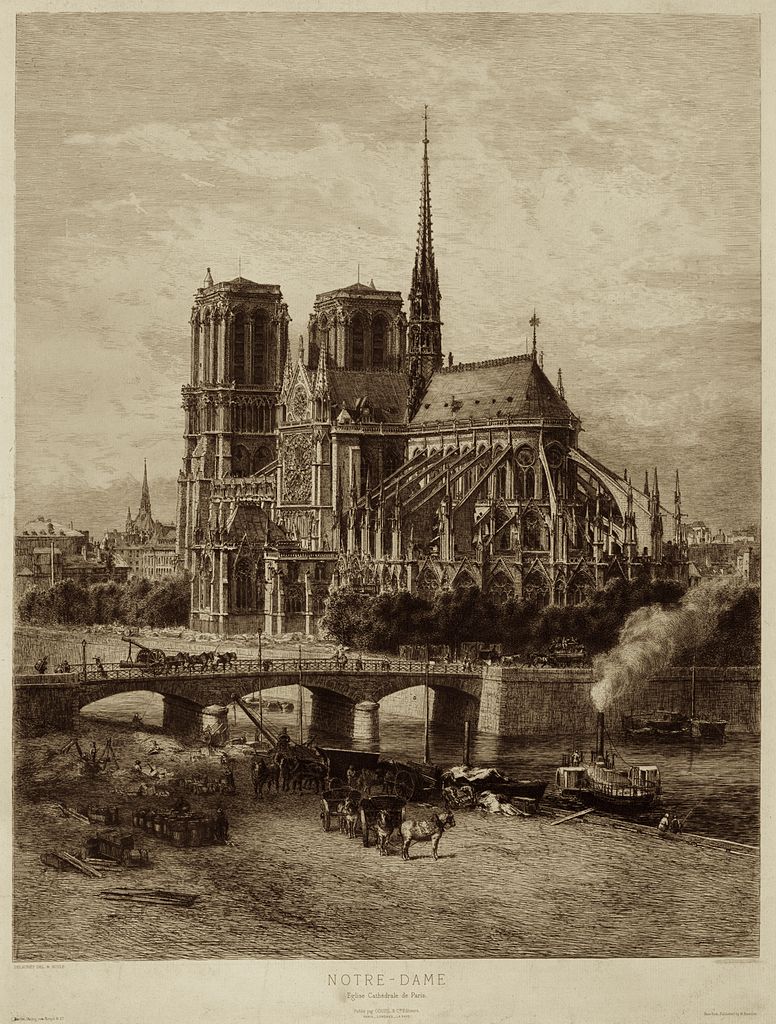

Nineteenth-century engraving of Notre Dame Cathedral by Alfred-Alexandre Delauney. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)