Industry in North America has changed enormously in the seven decades since World War II. Manufacturing has moved away from the industrial heartland of the northeastern and midwestern United States and eastern Canada, to other parts of the continent or overseas.

This process is commonly referred to as deindustrialization. I don’t like this term, because it seems to imply that the industrial revolution has somehow ended and moved on from a region or a country. Nothing could be further from the truth, at least not in the case of North America. The ex-industrial heartland of North America still has plenty of manufacturing—Ford Motor Company still has an enormous operation in Dearborn, Michigan, for example—and people living there continue to live by the clock, consume large amounts of energy, and use manufactured goods. The United States is no longer the world’s leader in manufacturing, but it holds the second place with a very comfortable lead over third-place Japan.

Yet even if the term deindustrialization is misleading, its effects are real enough. The closing down of a major operation in an industrial town can be traumatic, as the town loses a major source of tax revenue and the employees lose their jobs and union wages. The effect of industrial relocation is portrayed in a memorable (if maudlin) way in Michael Moore’s 1989 debut film Roger & Me.

Another example of industrial relocation appears in a book I read way back in my first semester of grad school: Capital Moves: RCA’s Seventy-Year Quest for Cheap Labor, by Jefferson Cowie. The book describes how the Radio Corporation of America moved its manufacturing from New Jersey to Indiana, Tennessee (briefly), and finally northern Mexico.

RCA made some of the twentieth century’s most popular consumer electronics products, radios and televisions. At its peak, it was one of most profitable companies in the country. Thirty Rockefeller Plaza in Midtown Manhattan, now called the Comcast Building, was originally named the RCA Building.

RCA opened its first factory in 1929 in Camden, New Jersey, just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. The factory produced radios, the hottest consumer electronic product of its day. Management had hoped that the largely female workforce of the factory would not be interested in unionization. When the workers did unionize after a four-week strike—and with help from Depression-era labor legislation known as the Wagner Act—management decided to set up a new facility with a new, non-unionized workforce in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1940. Over time, as RCA and other industries left Camden, the former industrial tracts of the city turned into a desolate wasteland of boarded-up factories.

At length, and after a short but failed venture in Memphis, Tennessee, RCA moved its manufacturing of consumer electronics out of the United States entirely, and across the border to Ciudad Juárez in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. The RCA operation in Bloomington finally closed down in 1998, after the laserdisc players manufactured there had failed to become popular.

Two months ago, I went to a conference in Philadelphia, and out of curiosity I skipped a few sessions and rode a train across the Delaware to check out the remains of RCA’s industrial empire in Camden. Like many cities in the old industrial heartland of North America, Camden is slowly being redeveloped, its old factories and warehouses being torn down or converted to new uses.

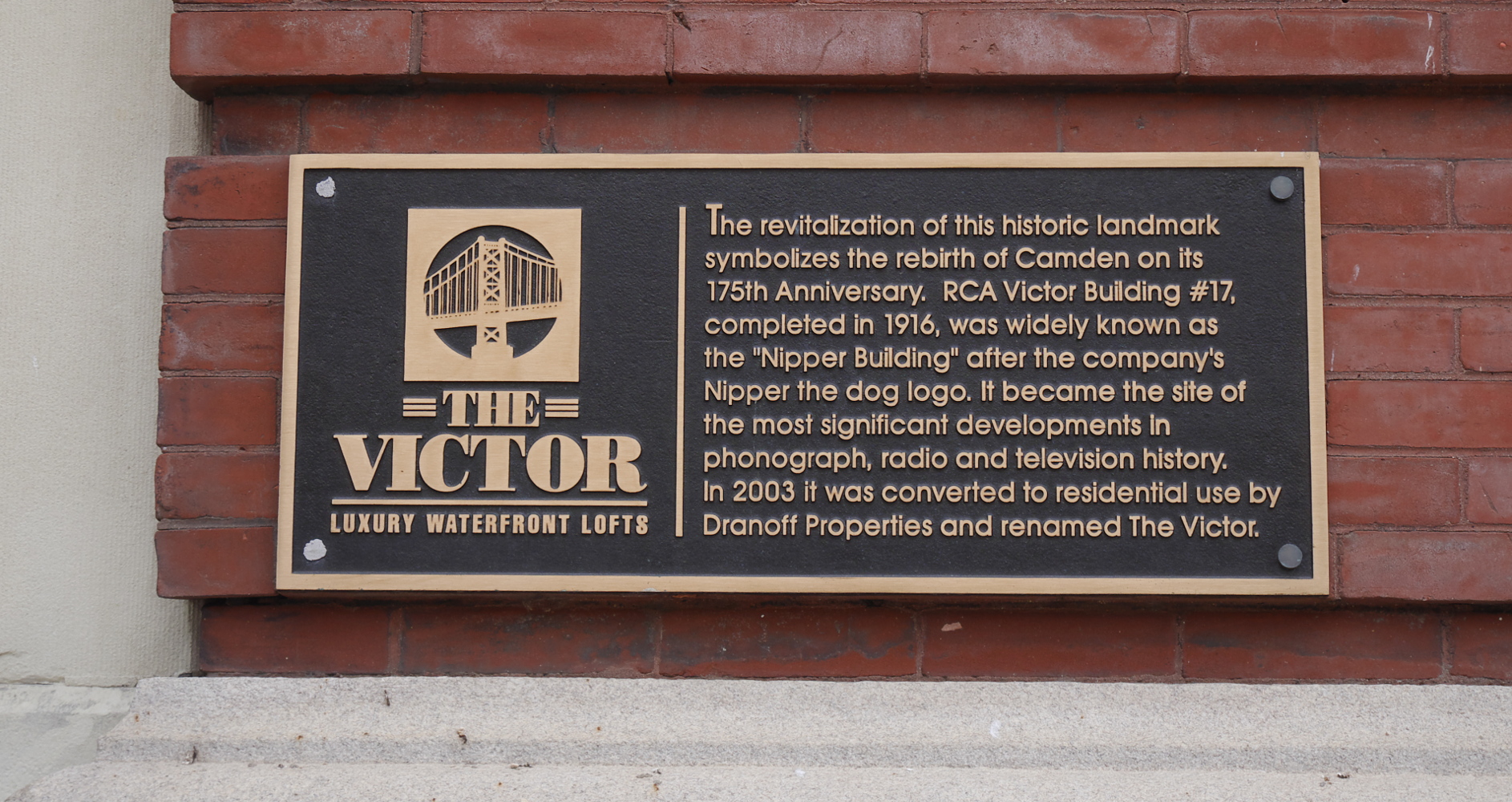

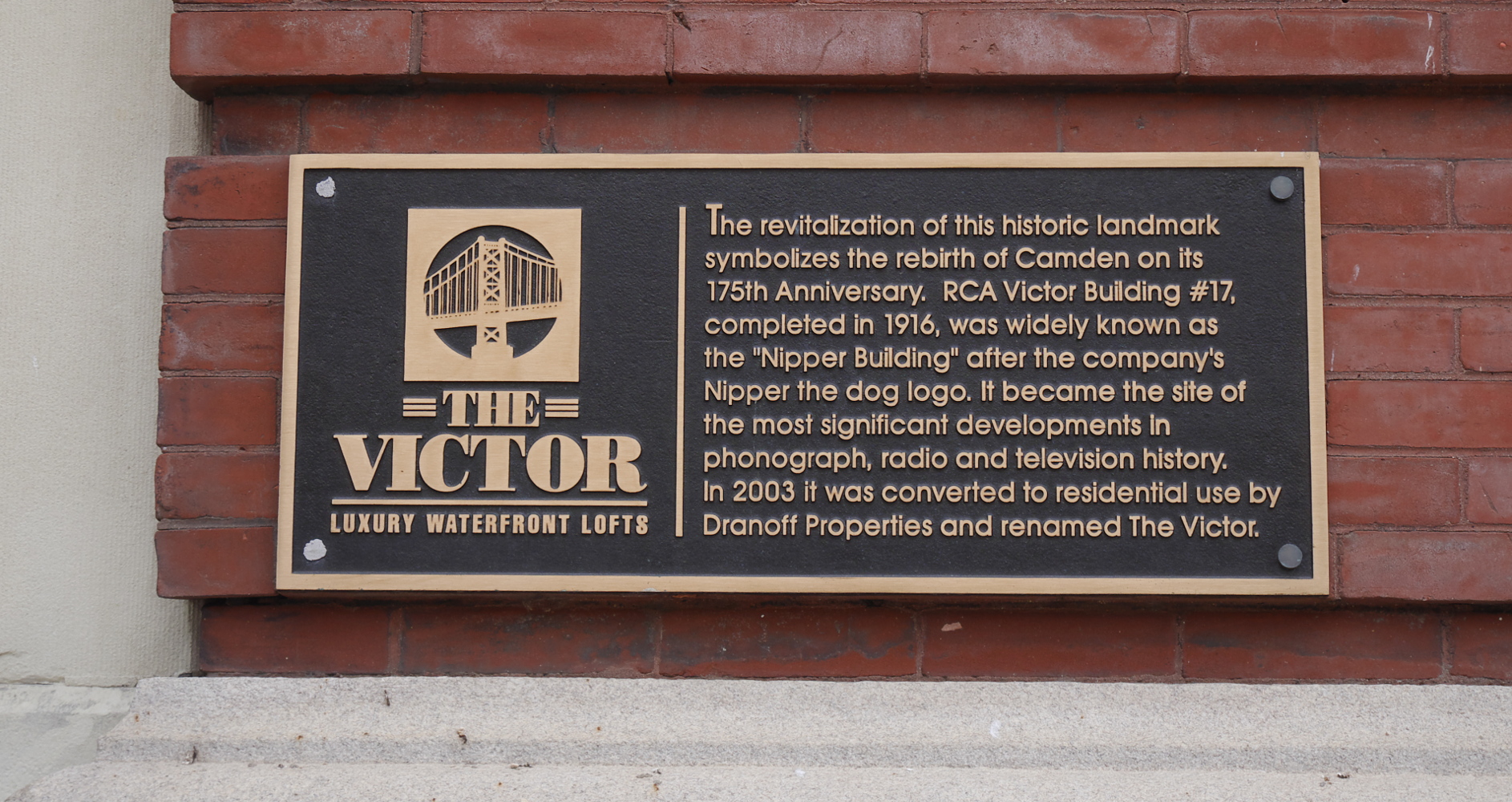

RCA Building #17 still stands tall above Camden, its ten-story tower visible from parts of Philadelphia. In 2003, it was converted into apartments, with some commercial space on the ground floor.

RCA Building #17 in its new incarnation as a luxury apartment building.

Detail of the tower of the RCA factory, with the company’s logo in stained glass.

Awning of The Victor, as the building has been rebranded.

Plaque on The Victor.

I am glad that the RCA factory was saved from the wrecking ball, although I wonder if the redevelopers could have come up with more creative uses for the building. As RCA Building #17 and its neighbors are transformed from boarded-up shells to luxury lofts, Camden is leaping from one urban crisis to another. The new urban crisis is caused by ballooning property values that make the city classist and segregated.

This is not a problem that I can solve in this short blog post—or anywhere. But it is something that should give pause to the redevelopers of old urban industrial sites.

New luxury lofts in the works in Camden.