Outside of Ciudad Obregon, in the northern Mexican state of Sonora, massive plots of cultivated land stretch for miles and miles into the distance. Agriculture on such a large scale is necessarily mechanized: tractors plow the fields, airplanes spray pesticides on the crops, mechanical harvesters pluck the wheat, and trucks carry the crops to town, from whence they are shipped to markets near and distant.

Watching over this agricultural activity with a look of intense determination is the statue of a young norteamericano, mounted on a monument within an agricultural research station outside of the city. The statue wears work boots, jeans, a brim hat, and a shirt with the sleeves rolled up above the elbows and the top two buttons undone. He is Dr. Norman E. Borlaug, and the research station where his statue is mounted is named in his honor.

American-born Dr. Borlaug is probably the most famous figure of the Green Revolution, an international movement in the 1960s and ’70s that dramatically increased crop yields in poor countries such as India and Pakistan. In the eighteenth century, Thomas Malthus had famously argued that since human population grows exponentially, populations must suffer violent reductions from time to time by famines or other disasters. Dr. Borlaug and other green revolutionaries realized that they could circumvent so-called “Malthusian checks” by exponentially increasing food supply to keep pace with population growth. Borlaug’s strategy was to selectively breed dwarf strains of wheat, which had shorter stalks and thus wasted less energy on growing the parts that humans can’t eat. To do this, he cross-bred wheat from his low-land station at Obregon with strains from a highland station in southern Mexico. (Researchers did similar work on rice at a station in the Philippines.) Borlaug’s dwarf wheat did produce higher yields than traditional strains, and for his efforts he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970.

The monument in Obregon personifies Borlaug as the Green Revolution. A low, curving wall in front of Borlaug’s statue bears the names of wheat varieties that he helped develop. On the back of the monument, an impressionistic relief shows women and children looking hopefully into the distance. The dedication plaque, with text in both Spanish and English, reveals that the monument is also a gravesite; Borlaug’s remains were interred here after his death in 2009 at the age of 95.

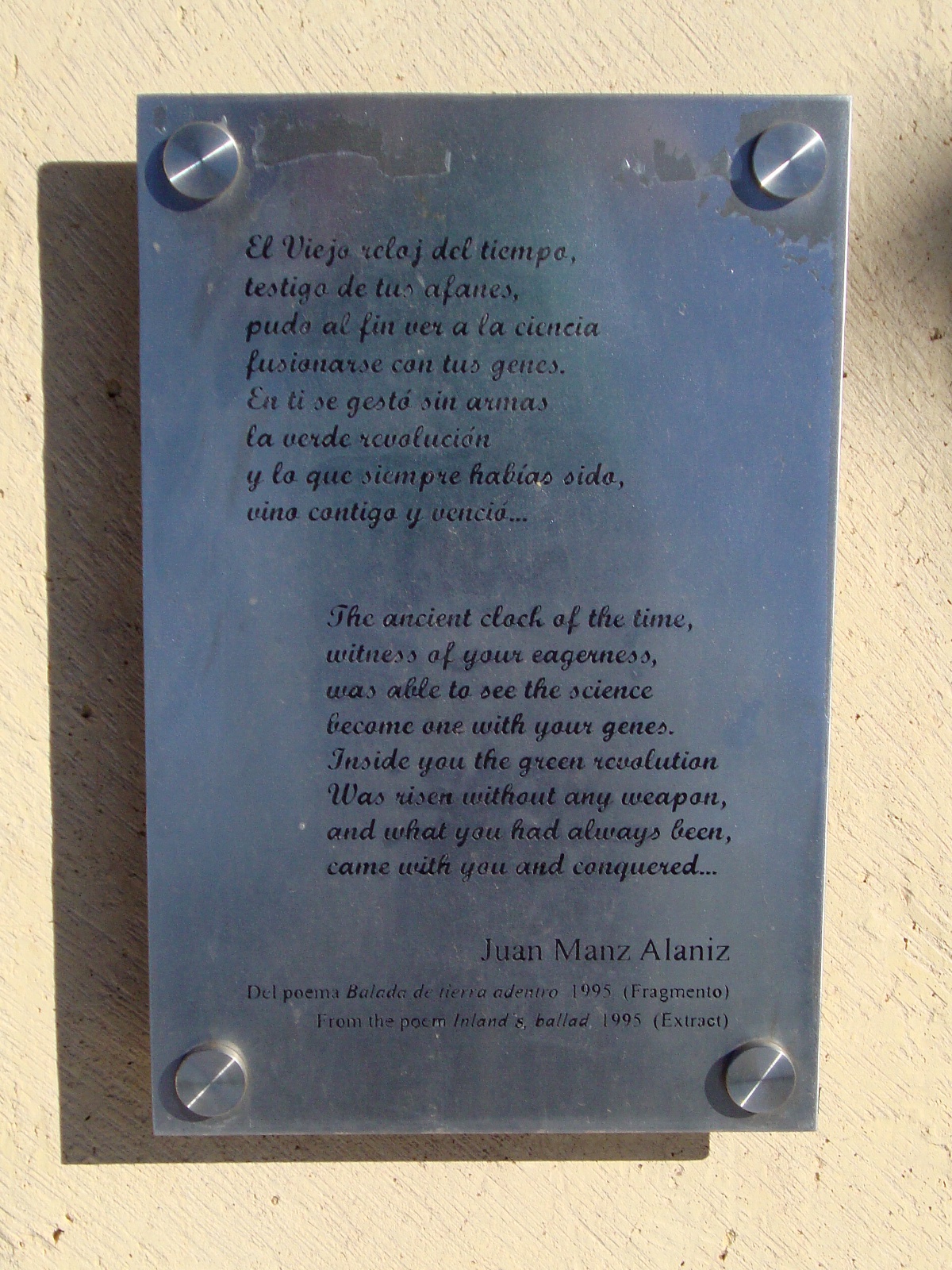

A bilingual plaque (not the dedication plaque) that personifies the Green Revolution as Dr. Borlaug.

The legacy of the Green Revolution is very much a part of our twenty-first century world. This legacy is problematic. Critics claim that the Green Revolution only delayed another inevitable Malthusian crisis. It also heightened environmental damage caused by industrialized agriculture. The Green Revolution was not “green” in contemporary parlance. It is not related to the organic farming movement; quite to the contrary, Green Revolution agriculture uses not only highly-specialized crop strains, but also pesticides and chemical fertilizers. It is therefore only fitting that across the road from the Borlaug research station there is an airstrip where several cropdusters are based.