Edwards Air Force Base, where the Air Force and NACA or NASA have tested experimental aircraft since before the Cold War, occupies a vast dry lakebed in the Mojave Desert in Southern California. Although the base lies just south of California State Highway 58, most of it isn’t visible from the road, because sight-lines are blocked by low hills and a railway embankment between the highway and the lakebed. One exception to this is Leuhman Ridge, which rises above the desert floor southwest of the junction of CA-58 and US Highway 395. Several large metal and concrete structures stand on the crest of the ridge, plainly visible from the highway miles away. These are rocket test stands, used in the Cold War and Space Race to test out new rocket engines and test articles of complete rocket stages.

The Air Force started out testing missile components on Leuhman Ridge in the 1950s. Missiles tested there included the Thor IRBM, the Atlas and Titan ICBMs, and the Bomarc cruise missile. Some of the test stands had large gantries that could hold complete missile stages like the Atlas. One of the stands, Test Stand 1-1, still has its gantry in place.

Test stands used for Air Force missiles on the western end of Leuhman Ridge. Test Stand 1-1 is on the left of the picture, with a large gantry that could hold a complete Atlas missile in a vertical position for tests. The stand on the right is 1-2.

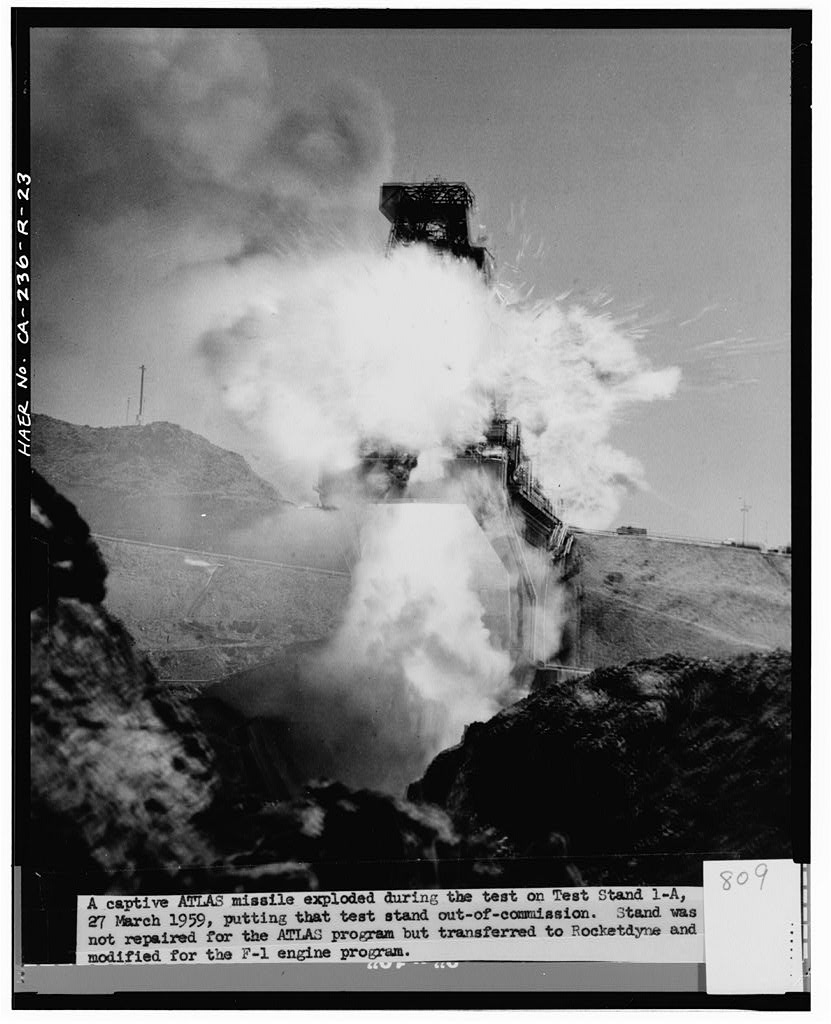

Photo of an Atlas missile exploding in Test Stand 1-A, March 27, 1959. The stand was never repaired for Atlas use but was instead modified for F-1 engine testing. (Source: HAER)

Subsequently, NASA and Rocketdyne tested the F-1 engine for the first stage of the Saturn V moon rocket on Leuhman Ridge. F-1 tests started on stands originally used for the Atlas missiles, then moved to purpose-built stands that were much larger than the earlier missile stands. Rocketdyne test-fired a prototype F-1 for the first time on February 10, 1961, before Alan Shepard’s first flight and before President Kennedy had committed America to the moon race.

F-1 prototype test-firing in stand 1-A. This test engine is firing without its nozzle skirt, or rear part of the nozzle. (Source: HAER)

The biggest of the F-1 stands was Test Stand 1-C, which could hold a pair of engines side-by-side. As tall as an 11-storey building, it had foundations deep into the granite bedrock of the ridge in order to withstand the power of the engines.

Test Stand 1-C during a test-firing of an F-1 engine in 1962. (Source: NASA)

Test Stand 1-C is the most prominent of the stands on Leuhman Ridge, because it now has a huge white building on top of it with an American flag painted down the side. Two similar test stands nearby, 1-D and 1-E, were also built for F-1 engine testing.

Apollo-era test stands on Leuhman Ridge: 1-D (L) and 1-C (R). Test Stand 1-C has been modified from its original configuration with the addition of a white tower on top, but 1-D looks about as it did in the 1960s. The large tanks directly behind and to the right of 1-C held water that was pumped over the flame deflector during tests. Test Stand 1-E is out of view on the other side of the ridge behind 1-D.

Since the Apollo-Saturn Program, some of the test stands have been modified for use on other programs. Even with the modifications, the stands are still visible relics of the Cold War and the race to the Moon.

Sources and links

- Roger E. Bilstein, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles (Washington, DC: NASA History Office, 1980), 121-122, 123-125. [HTML] [PDF]

- Ivan D. Ertel and Mary Louise Morse, The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology (Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Sapce Administration, 1969), 1:75. [PDF]

- https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.ca2576.photos?st=gallery Historic American Engineering Record of Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory

- https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.ca2594.photos?st=gallery Historic American Engineering Record of Test Stand 1-A at Test Area 1-120

- https://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?topic=25057.0 Forum discussion about Edwards Air Force Base rocket test stands