Recently, I was down in Southern California to do some research in the Water Resources Collection & Archives at UC–Riverside. On the way back north, I stopped in Montebello, east of Los Angeles, to visit the site of one of the last battles of the Mexican-American War in California, the Battle of Río San Gabriel. On the afternoon of January 8, 1847, Californio forces under the command of José María Flores tried to prevent American troops from crossing the San Gabriel River as they headed toward Los Angeles. Having read about the battle beforehand, I was able to picture the site in my head: a wide, shallow river, with a sandy bottom, bordered by willows on either side.

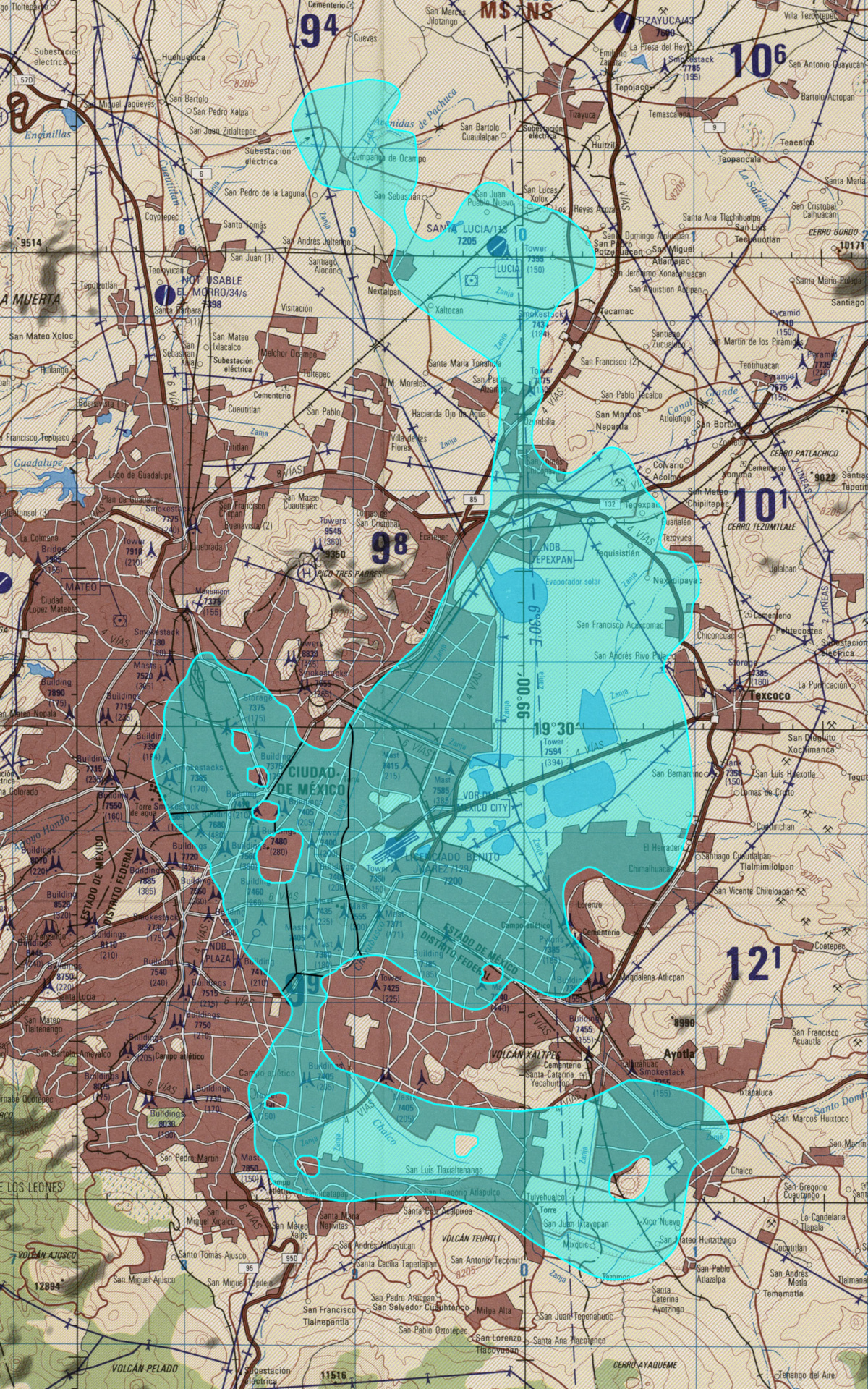

Painting of the Battle of Río San Gabriel by James Walker. The description of the picture identifies it as the Battle of Los Angeles, which was a different battle the next day (also known as the Battle of the Mesa). But I’m almos certain that this actually portrays the Battle of Río San Gabriel, because it matches the accounts of the battle, and doesn’t match the Battle of Los Angeles, which was a running engagement. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

What I saw instead was very different: a massive concrete channel, littered with trash but without so much as a trickle of water flowing in it or a blade of grass growing along its length as far as the eye could see.

What the Battle of Río San Gabriel site looks like now. (Note that this is actually the Río Hondo rather than the San Gabriel River; see below.)

I was surprised by what I saw, but I shouldn’t have been. Come to think of it, all of the rivers I had seen in the greater Los Angeles area were heavily engineered. The river in Montebello was a twin of the more-famous Los Angeles River (and in fact is a tributary of it). The Los Angeles River borders the downtown area and has hosted chase scenes in various movies (including Terminator 2). Looking down at the engineered river channel in Montebello, I couldn’t help but wonder:

Why are the rivers of Southern California so ugly?

When I got home, I found the answer in a book in my library. The book was The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth, by Blake Gumprecht. According to the book, the flow of the Los Angeles River varied widely between the seasons. During the dry summer months, the river would be a lazy, languid stream, meandering this way and that as it flowed down from the mountains to the sea near Long Beach. But in rainy winters, the river could become a raging torrent, washing away houses, farms, animals, and people.

Los Angeles proper was not vulnerable to flooding so much as the towns up- and down-stream of the city. As the Southland developed, and buildings and pavement took over land that used to absorb rainfall, the problem of flooding got to be more acute. Attempts to deal with the problem at the local level had limited success. Then the Depression came, and the federal government took over responsibility of flood control on the Los Angeles River. After a devastating flood in 1934, the Army Corps of Engineers began to channelize the Los Angeles River and line it with concrete. (An even more catastrophic flood in 1938 highlighted the need for better flood control measures on the river.) Between 1936 and 1959, the Corps channelized almost the entire length of the Los Angeles River.

Scene from the construction of the concrete channel of the Los Angeles River, 1938. (Source: UCLA Library Digital Collections, CC BY 4.0)

What about the site of the Battle of Río San Gabriel? Surprisingly, while the battle took place on the San Gabriel River, the river that flows by the site now is actually the Río Hondo, a completely different river! In 1867, before the flood control measures were built, the San Gabriel shifted its course to the east and the Hondo occupied the old channel of the San Gabriel. Flood control works on the Río Hondo and the modern San Gabriel River were built in the mid-20th century, at the same time as the Los Angeles River. The Army Corps completed the Whittier Narrows Dam on the San Gabriel River and Río Hondo in 1957.

The concrete river channels of the Los Angeles area were (and still are) marvels of engineering, but they are also ugly and obviously predate the modern environmental and beautification movements. Still, it’s hard to imagine Southern California without them, and we seem to be stuck with them for the time being.