Every country has its monuments, which glorify great men of the past (and less frequently, great women), commemorate battles won and lost, and represent the nation’s ideals. Even colonies have monuments, erected on behalf of the colonial power and often paid for by the subjects. When a colony declares independence, the monuments of the colonial power are often the first to be torn down. In 1776, American colonists toppled statues of King George III. After 1947, when India parted ways with the British Empire, statues of British monarchs were moved to museums or shipped off to Canada.

The now-empty pedestals in roundabouts and parks were soon occupied by statues of the new heroes of the independent nation: Mahatma Gandhi, Netaji Subhash, Pandit Nehru. Buildings and streets likewise received new identities: Kingsway in New Delhi became Rajpath, the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay became Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya. For that matter, Bombay itself was rechristened, becoming Mumbai. Just about the only thing that wasn’t renamed was the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata. A larger-than-life statue of the elderly sovereign remains in place in front of the wedding-cake building, but the interior now features a museum commemorating the independence struggle.

The example of India is not unique. Around the world, political changes usually lead to a flurry of renaming of streets and dismantling and rebuilding of monuments.

By comparison, the example of Singapore is unusual. Singapore has been an independent, sovereign nation for more than fifty years, but there has been little of the renaming and reinventing of the city-state that has happened in most other former colonies. A statue of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, who founded Singapore in 1819, still stands cockily over the waterfront. Most streets retain their colonial names. While there are plenty of historical markers for the colonial period and the Japanese occupation during World War II, there are no statues for Lee Kuan Yew, the country’s first prime minister—even though he served for more than thirty years and was a central figure in the modernization of the city-state.1

On first blush, it might seem that modern Singapore is lacking in a sense of identity, which other former colonies have gone to great lengths to cultivate. I certainly felt that way when I visited two years ago. But on further reflection, not having statues of modern heroes all over the place is a part of Singapore’s identity. It shows that the country is open to the world—or at least the modern, prosperous parts of it. With its gleaming high-rises and booming economy, Singapore itself is a monument to Lee Kuan Yew.

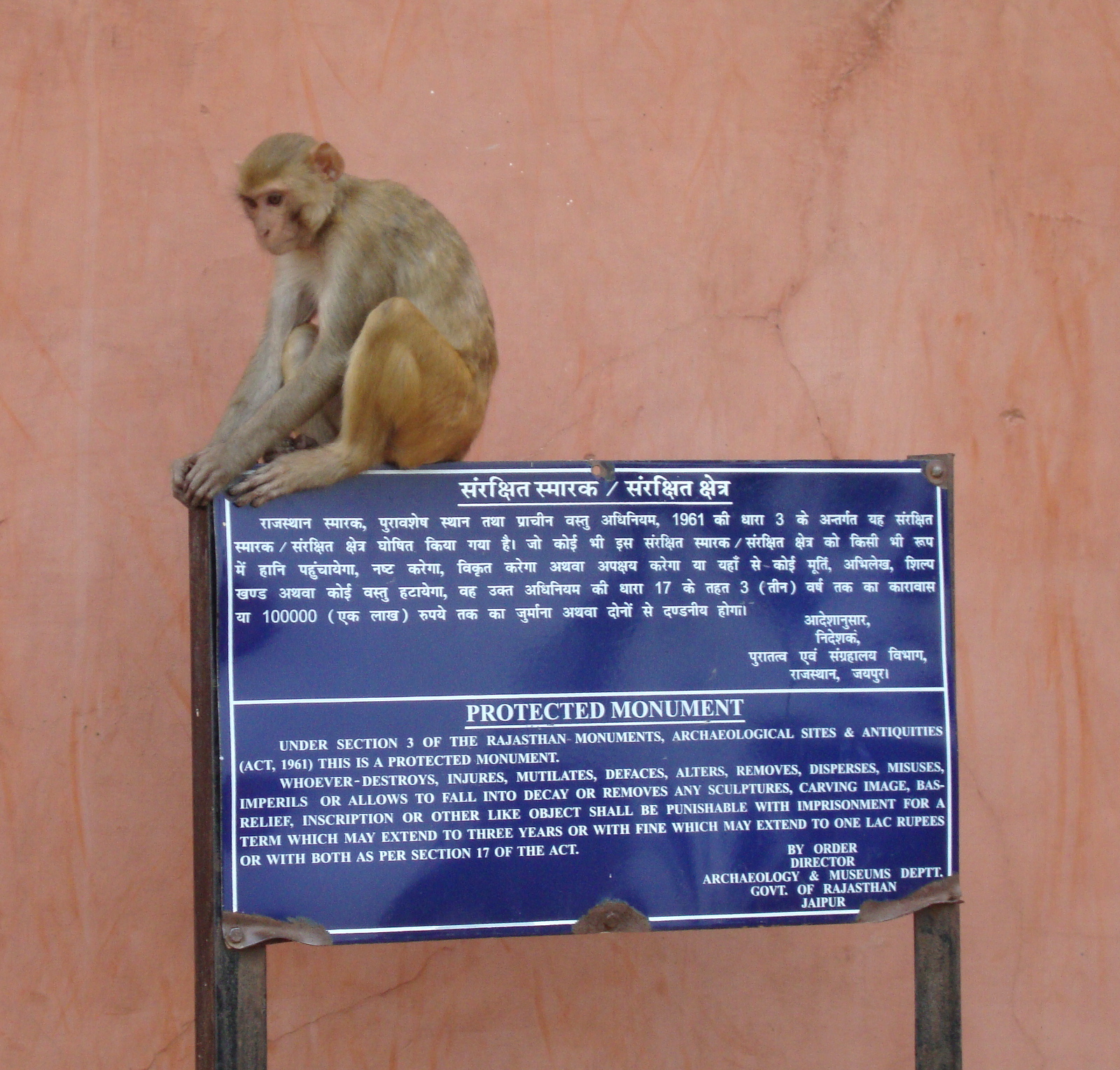

A sign on Connaught Drive, pointing to a historical marker about World War II. (The marker is located on the site of a memorial for the Japanese-affiliated Indian National Army, which was dynamited by Mountbatten’s troops after they retook Singapore in 1945.)

- C.M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore (Oxford, 1988), 320-21. [↩]