I recently watched the 1959 British movie North West Frontier, which was released in the United States under the title Flame over India. The movie is about a team of colonialists (including one American, played by Lauren Bacall) who, along with a couple of trusted Indians, spirit a rajkumar (prince) out of harm’s way when a native state is overwhelmed by rebels in early twentieth-century India. Most of the action takes place in and around a train, powered by a shunting locomotive, which is used to bring the prince to safety. I must say that I enjoyed the film for the most part. With one very notable exception, the movie holds up well after all of these years. The plot is interesting and the pacing is particularly good. There are also some impressive location shots.

My favorite part of the movie is the first ten minutes, during which the rebels attack and kill the raja, while the rajkumar and his caretakers narrowly escape. Hundreds of refugees swarm into the British fortress before the doors are forced shut, leaving hundreds more stranded outside. The scene is dramatically shot, with a huge cast of extras. Except for opening narration, the first ten minutes have no dialogue. The action carries the story forward.

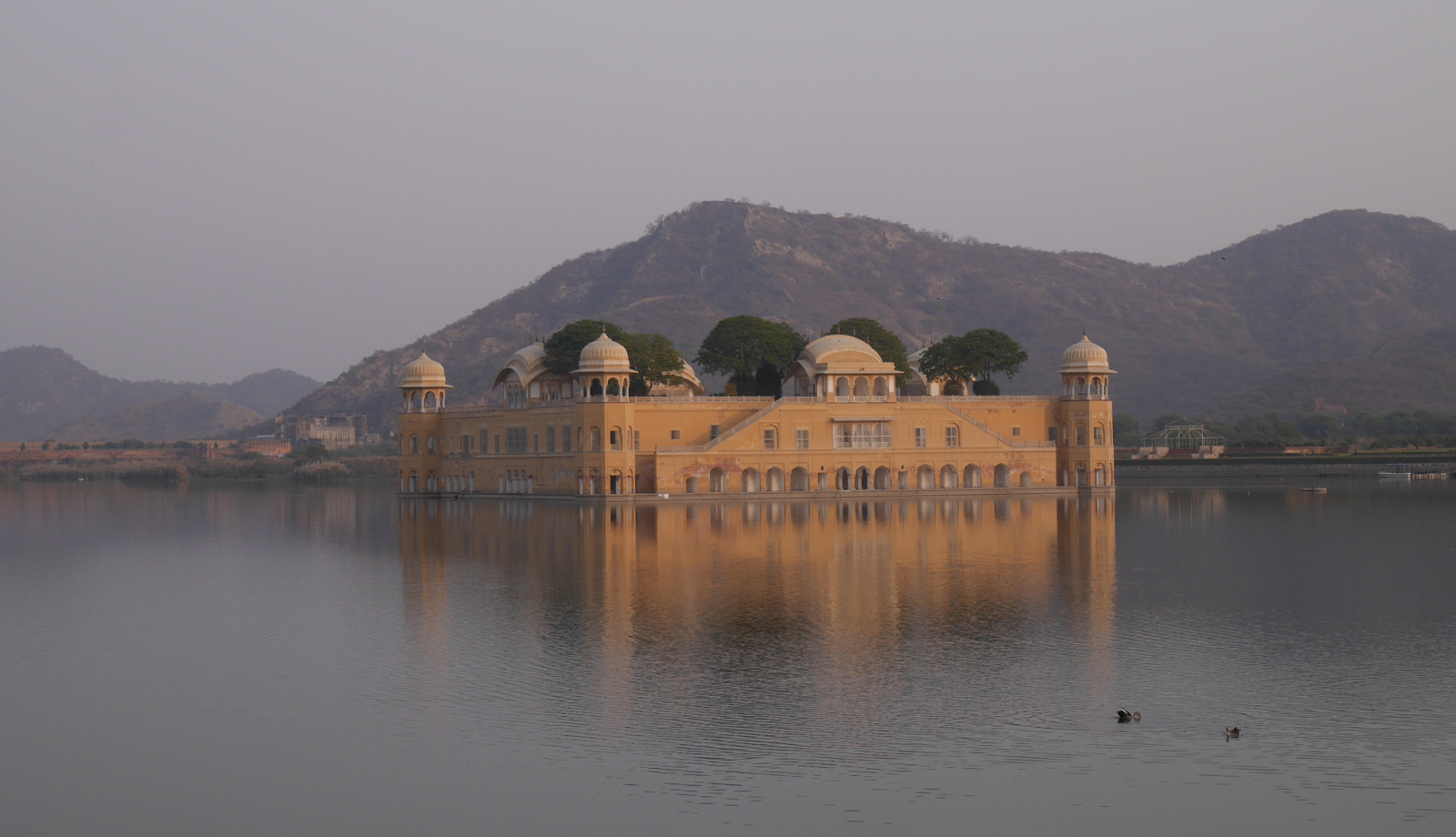

Even though the story is set somewhere in the North-West Frontier Province, now part of Pakistan, the opening scene was shot around Jaipur, in the Indian state of Rajasthan. It is very identifiable for those familiar with the area. The raja’s palace is Jal Mahal, an iconic lake palace visible from the road to the old capital of Amber. In the 1950s, the lake was low and Jal Mahal stood on dry ground, allowing the stuntmen rebels’ horses to gallop right up to it. Since then, the dam has been refurbished and the palace once again appears to float in the lake.

The British fortress is none other than Amber Fort, one of India’s most famous castles. It was built over the course of a more than a century, starting in the 1590s. In 2013, UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site.

Also in Amber, there are views Jagat Shiromaniji Temple (built 1599-1608), Charan Mandir, and a lake behind Jaigarh fort.

The heroes’ approach to the British fort gets a little distracting for those familiar with Amber, because they take a route that doesn’t make sense. They head north through a valley on the back side of the fort, then cross the ridgeline south of the fort, and yet somehow manage to arrive at the front gate on the east side.

Most of the train scenes were actually shot in Spain, although the Spanish landscape is enough like Rajasthan to be believable. The train spends plenty of time passing through a valley that made me think of taking Amtrak through the California Central Valley, with the high Sierra in the background.

The one respect in which the film is really dated is its religious stereotyping. The rajkumar, Prince Kishan, is Hindu; the rebels who storm his kingdom and slaughter his father are Muslims. The rebels intercept the train at various points in the story, sometimes galloping up on horseback like Comanches in a western movie. There is also a Muslim character on the train, who turns out to be the story’s chief antagonist, apart from the faceless rebels. Mr. Van Leyden is a journalist who insinuates himself into the train’s crew. After he refuses whiskey, another character asks him if he is Muslim, and he admits that he is. He claims that he is of mixed Indonesian-Dutch heritage – hence his name. The story leaves it unclear whether this is actually the case, because later Van Leyden claims to be half-Indian and fighting for the freedom of his nation, an all-Muslim nation. In his makeup for the role, Herbert Lom, the Czech-born actor who plays Van Leyden, looks credibly half-Indonesian. He does not look half-Indian.

From his position in the train’s crew, Mr. Van Leyden tries to assassinate Prince Kishan. He fails and is defeated in the film’s climax. If Mr. Van Leyden really is half-Indian, the stereotyping of Indian Muslims all as rebels is bad enough. But if he is half-Indonesian, then this is most problematic because it suggests that all Muslims are like him and have a similarly violent nationalist or pan-nationalist agenda.

Mr. Van Leyden is the one postcolonial voice in the cast. When the British leader of the expedition, the daring Captain Scott (Kenneth More), dismisses the rebels as children, a standard colonial trope, Van Leyden retorts that they are grown men – uneducated, yes, but men nonetheless. Van Leyden represents the educated, privileged elite of colonized nations, who were proud of their nation but had also absorbed colonial critiques of it. The character has several good lines in the movie, but unfortunately his ideas are all discredited by his revelation as the villain.

No Muslim characters are portrayed positively in the movie. That this movie isn’t just a colonial fantasy becomes clear in one scene. At the beginning of the movie, the last regular train makes it out of the besieged city; later, the special train carrying Prince Kishan comes across the first train stopped at a station. Its passengers have been killed to a man. Lauren Bacall’s character walks through the three train cars, full of corpses with flies buzzing about them, as vultures flock overhead. The scene is dramatic, and part of what makes it so chilling is how real it is. The film was made only twelve years after Partition, when exactly this happened. In the movie, Muslims kill a trainload of Hindus. In real life, adherents of both religions killed members of the other religion in huge numbers. In the movie, Hindus are portrayed as totally nonviolent – or in the case of the soldiers on the train, acting only in self-defense. As history would show, Hindus could be just as violent as Muslims.

It is this bad portrayal of Muslims that has kept North-West Frontier from becoming a classic, and rightly so, because in America and India (and definitely other parts of the world), the last thing we need is more negative portrayals of Muslims. It’s a shame too, because the film is good otherwise.