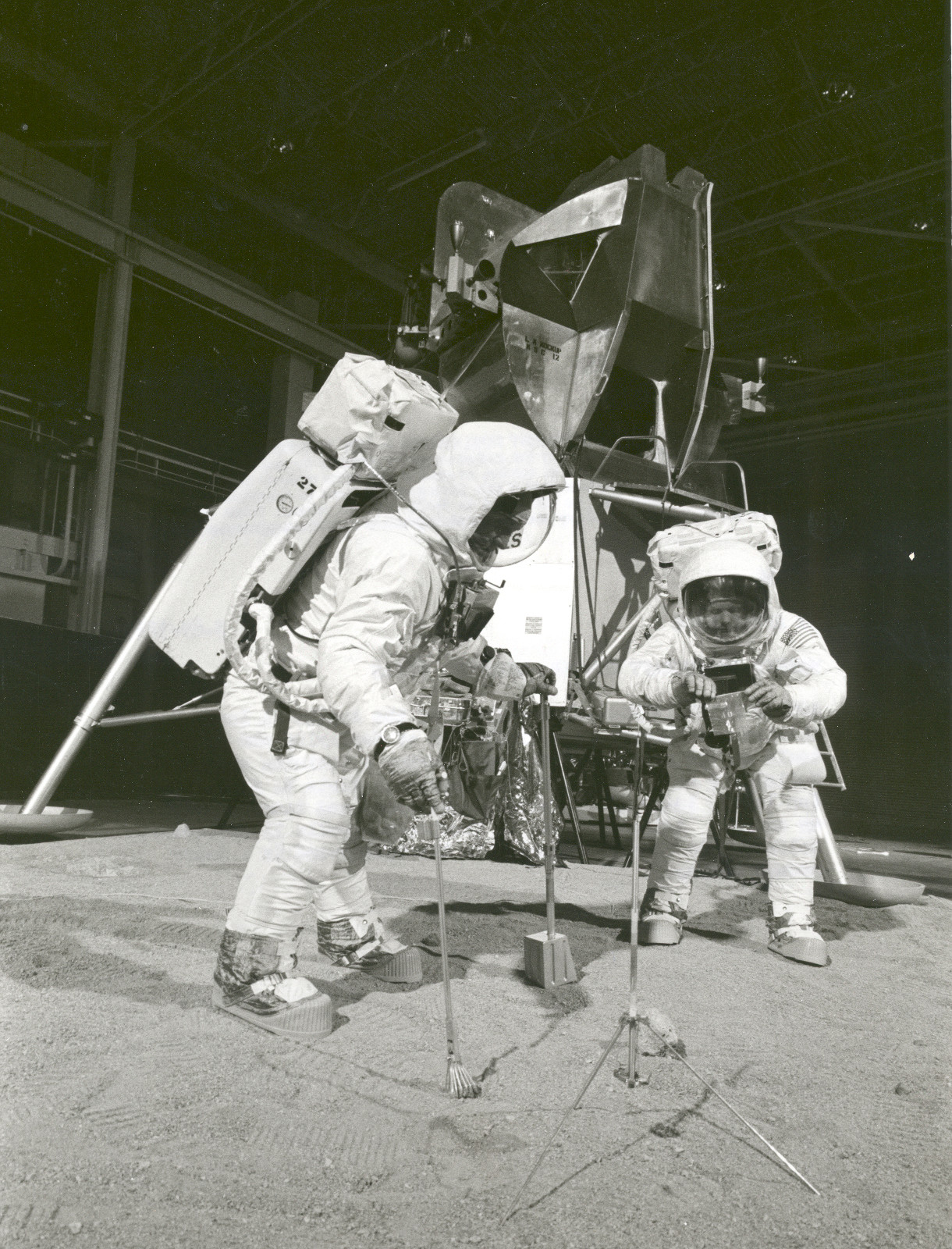

Fifty years ago this month, men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon. They came in peace for all mankind.

The fiftieth anniversary of Apollo 11 has gotten a lot of publicity, more than I remember the thirtieth and fortieth anniversaries getting. There seem to be two dominant ways that companies and institutions are commemorating the fiftieth anniversary. One is marketing collectibles. Estes, the model rocket manufacturer, has reissued classic kits of rockets from Mercury to Apollo. LEGO has released large and detailed sets of the Saturn V and Lunar Module.

The other dominant way to commemorate Apollo 11 has been to use the anniversary as an occasion to discuss the future of space travel. The cover of National Geographic this month declares, “A new era of space travel is here,” and USA Today last week carried the headline: “Fifty years ago, Apollo 11 made the world a bigger place. NASA is ready to go back.”

In some respects, this preoccupation with the future is understandable because space travel has long been imagined as futuristic. Spaceflight was envisioned in science fiction long before it became a reality. Even after people had begun to fly into space, true believers in space travel continued to dream big and kept claiming that the next big thing was just around the corner: inexpensive access to low Earth orbit with reusable spaceplanes, permanent moon bases, and nuclear rockets flying to Mars and beyond.

None of these things have come to pass. The Space Shuttle, though reusable, proved to be expensive to maintain and risky to fly. Moon bases have never been built, and nuclear rocket propulsion remains science fiction. (In a May 25, 1961 speech, just after famously calling for the United States to commit to a moon landing by the end of the 1960s, President John F. Kennedy exhorted Congress to appropriate funds to accelerate the development of the ROVER nuclear rocket—but who remembers that?)

There is a real irony about the future-looking coverage of the moon landing anniversary: space travel belongs to the past as much as to the future. Both National Geographic and USA Today put photos of the Apollo program on their covers, to introduce their articles about the future of space travel. The graphic designers at National Geographic even went so far as to frame the Apollo 8 earthrise photo they used with film sprocket holes—further emphasizing Apollo program’s belonging to the past, because the vast majority of photography in the 2010s is shot digitally rather than on film.

It was literally a half-century ago that men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon. We can certainly look forward to further human exploits in space (although considering that we still have no moonbases and nuclear rockets, I won’t hold my breath). But an imaginary future in space should not distract us from the real past. Apollo 11 flew a long time ago, taking off from and landing on a world that was very different than it is today.