In 1969, the model rocket company Estes Industries introduced a kit called Orbital Transport. The rocket consisted of two parts, a larger carrier rocket and a small glider. When launched vertically from a standard model rocket launch pad, the carrier rocket would take the glider up to altitude, and then the glider would detach and glide back to the ground while the carrier rocket descended under a parachute.

My Orbital Transport, which I built from plans in 2000 and flew just once in 2003. The markings are hand-painted rather than using decals, which I didn’t have.

The 1969 Estes catalog had this to say about the design of the kit:

Spectacular in flight and a true show model on the ground, the Orbital Transport is the launch vehicle of the 80’s. Based on the latest proposals for a reusable air breathing (scramjet) booster for orbital vehicles, the Transport is an exciting experience to build and fly.

What were these “latest proposals” that the catalog referenced?

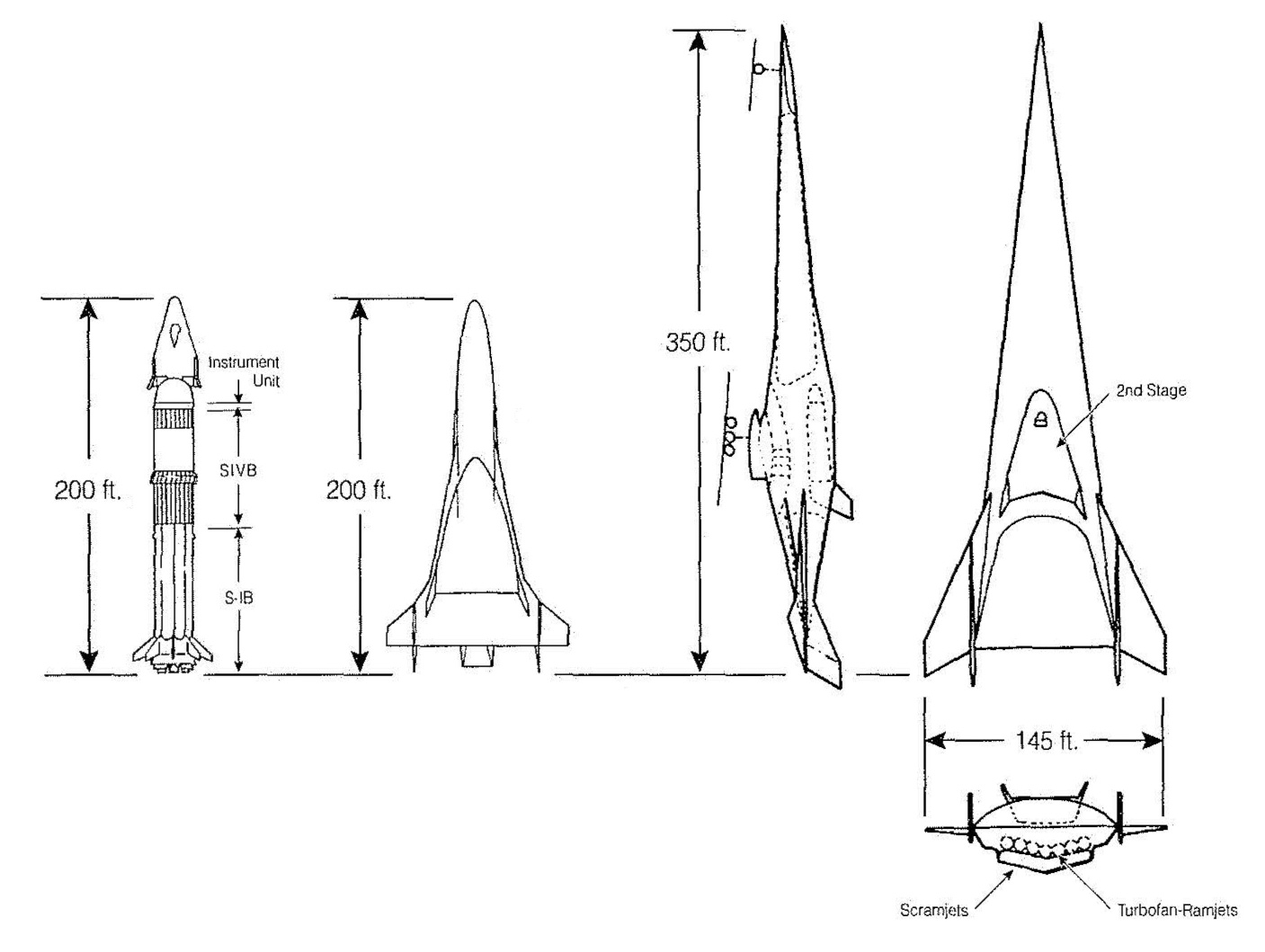

Between August 1965 and September 1966, a joint NASA-US Air Force panel studied the possibility of building spaceplaces to succeed the expendable boosters and single-use capsules that were then launching people into space. The panel studied three classes of spaceplanes, namely:

- Class I: A reusable spaceplane launched atop an expendable booster, such as the Saturn I-B or Titan III-M.

- Class II: A fully reusable two-stage spaceplane, both stages winged and both powered by rocket engines. The orbital second stage would ride piggyback atop the suborbital first stage.

- Class III: Another two-stage spaceplane, similar to Class II, but with air-breathing engines (scramjets) in the first stage.

Three different types of spaceplanes studied by the joint NASA-USAF panel in 1965-66 (L-R): Class I, launched atop a Saturn I-B booster; Class II, with two reusable rocket-powered stages; and Class III, with a scramjet-powered first stage. Class III is shown on the right in a three-view. (Source: USAF illustration printed in Heppenheimer, The Space Shuttle Decision, p. 83)

The panel envisioned all of these spaceplanes flying, one after the other, with the technology developed in one class being used in subsequent classes. In the panel’s optimistic timeline, Class I would fly by 1974, Class II by 1978, and Class III by 1981.1

The joint NASA-USAF panel issued its report in 1966, three years before Estes introduced the Orbital Transport. The design of the Orbital Transport kit is clearly based on the Class III spaceplane, and several details of the kit are drawn directly from the 1965-66 study. The carrier rocket, which represents the first stage of the Class III spaceplane, has open boxes under its “wings” (fins), which represent air-breathing scramjet engines. The 1980s date for the design (as the catalog description says) is also from the study, because Class III was supposed to be flying by 1981.

The Estes model rocket design included one fanciful element that was not present in the NASA-USAF study. While Class III was intended for launching satellites and possibly servicing a space station, Orbital Transport was a passenger transport, a space-airliner. The decal set that came with the kit identified it as being operated by “Astron Aerospace Lines,” and the decals for the glider had a row of windows with a stripe through them, like the airliners of the 1960s.

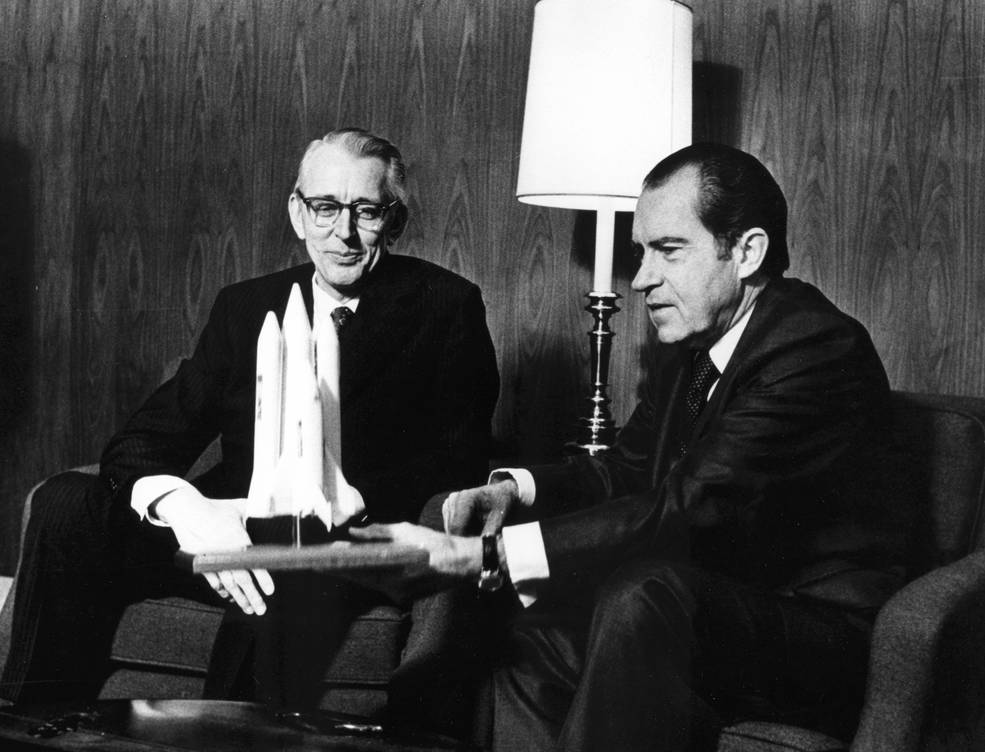

The NASA-USAF study proved to be fanciful as well. More than 55 years after the panel issued its report, a spaceplane like Class III has never been seriously considered. In the latter half of the sixties, NASA tried hard to make the Class II design work, but it was too big and too expensive, and the engineering challenges inherent in its design were too great. NASA at last fell back on a version of Class I, and in January 1972 (fifty years ago this month), President Nixon approved NASA’s plans to build a reusable spaceplane with a partially reusable booster—what would become known as the Space Shuttle. The shuttle first flew in 1981, the year that the vastly more sophisticated Class III spaceplane was supposed to start flying.

President Nixon (R) meeting with NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher to approve the Space Shuttle program, January 5, 1972. (Source: NASA)

The Space Shuttle concept as it appeared when initially approved in 1972. The basic elements of the design are all in place, but the liquid-fuel boosters pictured here would be replaced by solid boosters in the shuttle as built. (Source: NASA)

The Estes Orbital Transport has been out of production for a long time (except for a brief reissue in the early 2000s), but Semroc makes a reproduction of it. I made my Orbital Transport by “cloning” it, which means that I built it from plans using stock parts (rather than using a kit, which wasn’t available at the time). I got the plans from JimZ Rocket Plans.

- T.A. Heppenheimer, The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA’s Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle (Washington, DC: NASA History Office, 1999), 82-83. [↩]