Something I’ve noticed when studying languages is that loanwords from that language in English don’t always mean the same thing in the donor language as they do in English.

An example: “jungle” comes from a Hindustani word meaning forest. In India, a jungle could be any forest—from the dense tropical forests that the name connotes in English, to the thorn-forests of central India, or even the coniferous forests of the foothills of the Himalaya.

Another example: “sombrero” is of course a word that American English has picked up from Mexican Spanish, but again the word has a broader meaning in the donor language than in English. For English-speakers north of the border, a sombrero is a particularly Mexican kind of hat, with a very broad brim. But south of the border, a sombrero is any kind of hat—or at least, any kind of hat with a brim.

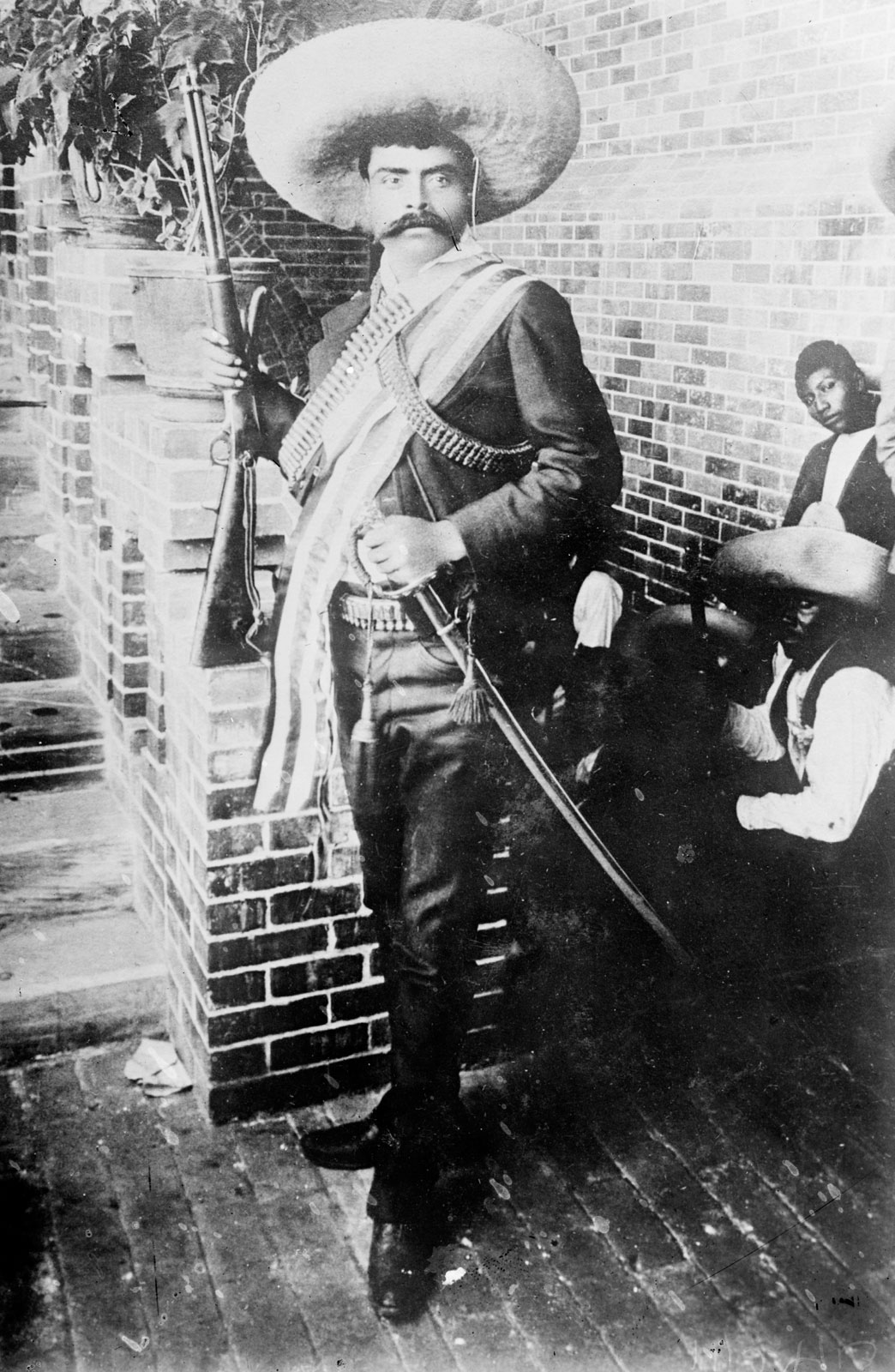

Now that is what I would call a sombrero. (Emiliano Zapata from Wikimedia Commons)

The hat your blogger is wearing is a sombrero in Spanish but not English. (Teotiuhuacán, Estado de México)

I think of the adoption of loanwords as a bit like technology transfer: the meaning of the word changes as it moves from one language to the next, just as the form and function of a technology have to change to fit the recipient culture.

In the case of both jungle and sombrero, the meaning of the word in English is linked to the culture that the word came from. India has its share of dense tropical forests, and Mexico has—or at least had—many of the traditional wide-brimmed hats. English already had a generic word for forest and hat, but it was in the market for a specific word to represent forests in (parts of) India and hats in Mexico.