In 2014, I spent part of the summer in Washington, DC, researching for my dissertation at the National Archives and Library of Congress. On weekends and some afternoons, I explored the city and surrounding region, and I even made longer trips to Pennsylvania and New York. As I traveled around, I kept running across sites or artifacts associated with the American Revolutionary War. The more I saw and read about the Revolution, the more I became aware of how little I knew about that part of history.

I made up my mind to read The Glorious Cause, by Robert Middlekauff, the volume of the Oxford History of the United States about the Revolution. The book is long, so it took me a while (I had to take a lengthy break in the middle), but it was worth reading, because I learned much that I, as a historian of the twentieth century, had never before had occasion to learn. (Since my fateful summer of 2014, interest in the Revolutionary War has gone mainstream, thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda and Hamilton.)

While reading The Glorious Cause, I was particularly fascinated by Middlekauff’s narrative of the Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn—an engagement I had never heard of before. The Battle of Brooklyn (August 26-30, 1776) was the first major military engagement of the American Revolution after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence two months earlier. British troops, under the command of General William Howe, landed on Long Island and attacked the Americans under George Washington. (These events are covered in the Hamilton song “Right-hand Man.”) The American forces were protected behind the hills known as the Heights. The passes nearest the American positions in Brooklyn (then a village independent of Manhattan) were well defended, but the British circumvented the defenses by taking the lightly-defended Jamaica Pass to the east. A contingent of Marylanders died holding the main body of the British troops off at the Vechte farm, but most of the rest of Washington’s army escaped across the East River to Manhattan, surviving to fight another day.

In the 240 years since the battle, Brooklyn has grown to engulf the farmlands and woodlands where British and Continentals clashed. Scattered around the borough are sites associated with the battle, some marked with plaques, others not (but all listed in detail in this comprehensive guide). In addition to gentrified brownstones, hipster lofts, and forbidding project housing, Brooklyn has its own Revolutionary War battlefield. Brooklyn has it all.

In March this year, I spent a day exploring Brooklyn, looking for sites that had to do with the battle or the Revolution in general. I found two sites particularly interesting.

The first was Prospect Park, site of a pass where American troops were routed by Hessian mercenaries fighting on the British side. The park, designed by Frederick Law Olmstead (whose other credits include Central Park in Manhattan and the US Capitol grounds) preserves part of the landscape of the battlefield, which has been lost under buildings and streets most everywhere else in the borough.

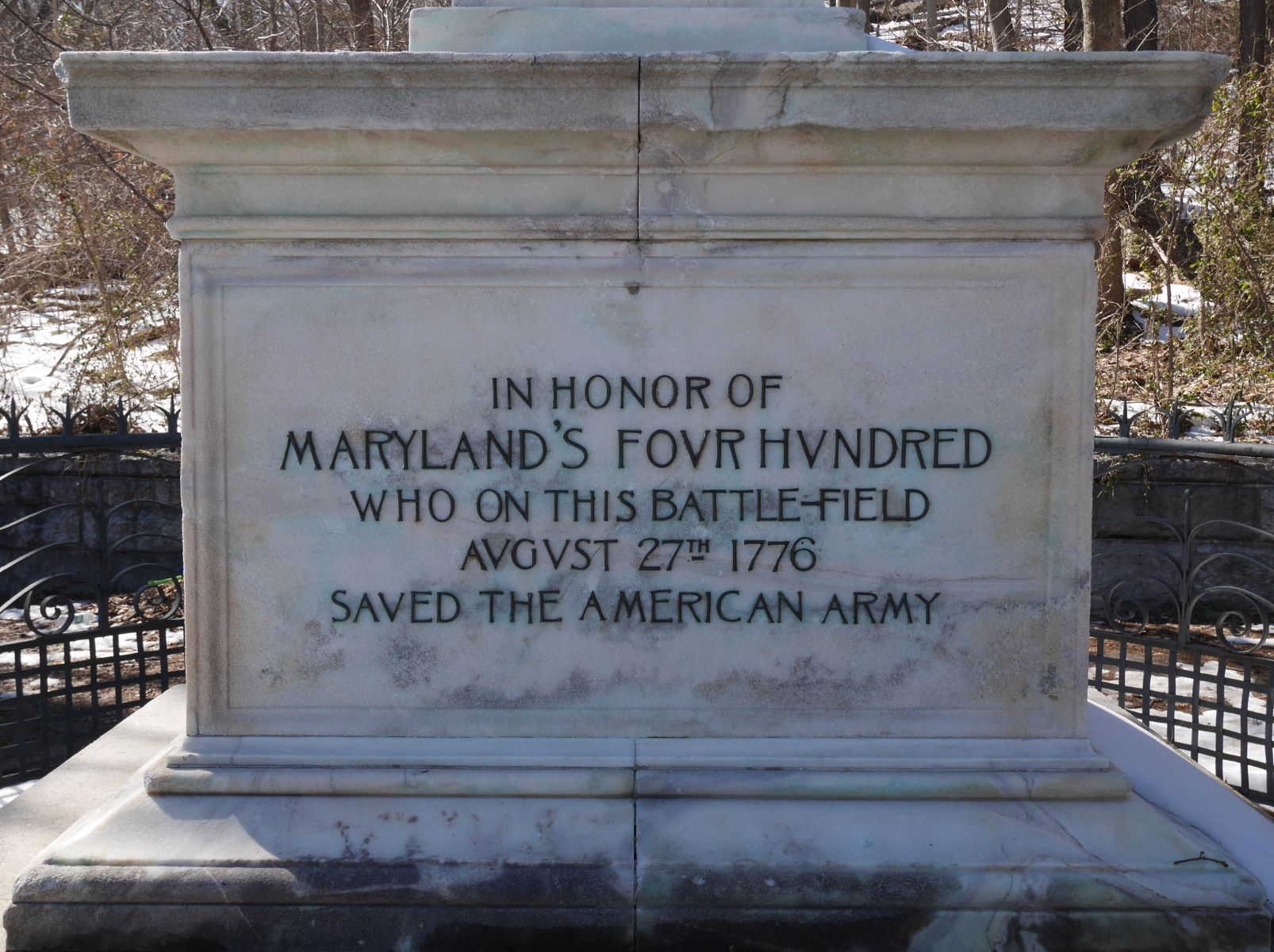

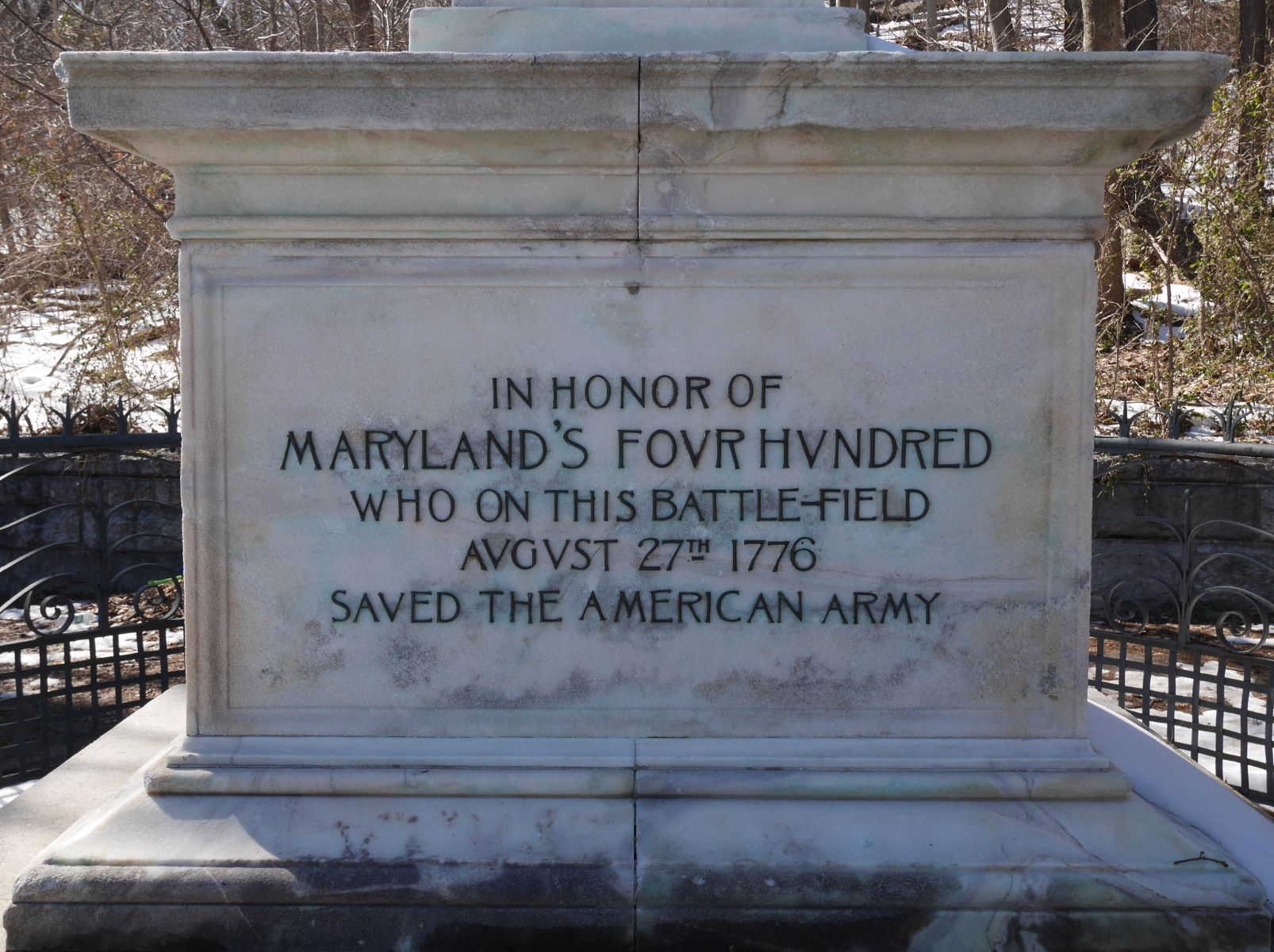

On a hillside in the park stands a monument to “Maryland’s Four Hundred,” who fell holding back the British (or “saved the American army,” in the exaggerated wording of the monument). The mention of the number of Marylanders is a not-so-subtle reference to the Three Hundred Spartans, who held the Persian army off at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, while the armies of other Greek city-states escaped to regroup and ultimately defeat the Persians. The placement of the monument to 400 Marylanders in the park, near the battle pass, is another reference to Thermopylae, because the Spartans died defending a pass. But despite the monument’s claim that the Marylanders performed their great deed “on this battlefield,” they did not fight in a pass; they fought on a farm, more than a mile from the monument.

Memorial to “Maryland’s Four Hundred” in Prospect Park, Brooklyn.

Misleading inscription on the memorial to “Maryland’s Four Hundred.”

The site of that farm is the other especially interesting site related to the Battle of Brooklyn. The old farm is also a park—not a grand park like Prospect, but a small municipal park with a playground and athletic fields. In the middle of the park stands the Old Stone House. Originally built in 1699, the Vechte Farmhouse went to ruin and was demolished around 1900, but then in the 1930s the stones were dug up and the house reconstructed from drawings. The ground floor contains a small, free museum about the battle and its context.

The reconstructed Vechte farmhouse, Washington Park, Brooklyn.

The Old Stone House isn’t exactly the Vechte Farmhouse that stood there during the battle. It is a twentieth-century building made of seventeenth-century parts. But that doesn’t matter to me. What does matter is that there is plenty of continuity with the past, there and at other sites associated with the Battle of Brooklyn. There may be no national park for the battlefield, as there are for Saratoga and Yorktown. Instead, remnants of the eighteenth-century battle and its memorialization live on in twenty-first-century New York City.